By Meghaa Gupta

The wildings (stray cats) of Nizamuddin are in a frenzy. An unknown cat is invading their minds with its thoughts… Mara is scared, put me down! Where did my mother go? Where are you taking me? Don’t want to leave the drainpipe! You’re frightening Mara… It needs to be silenced, once and for all. Except, this intruder a.k.a ‘the sender’, is but a tiny, terrified kitten and Beraal, the cat sent to kill it, can’t bring herself to do this. Instead, Beraal fights her clan and chooses to train Mara to control her sending – a power that is as rare as its precious, for it allows Mara a free pass into the minds of all cats, including the big ones in zoos!

Soon, the wildings find themselves developing a grudging respect for the orange kitten with monsoon green eyes. But there is one big difference between Mara and the wildings – Mara is an ‘inside cat’. She lives in ‘bigfeet’ (human) territory and finds no reason to leave it. After all it’s a comfortable existence. Rich, warm meals without hunting, digging through garbage and suffering the vagaries of weather. Besides, her bigfeet are nice. And therein lies an essential tension that the novel explores: the place of human beings in the natural order.

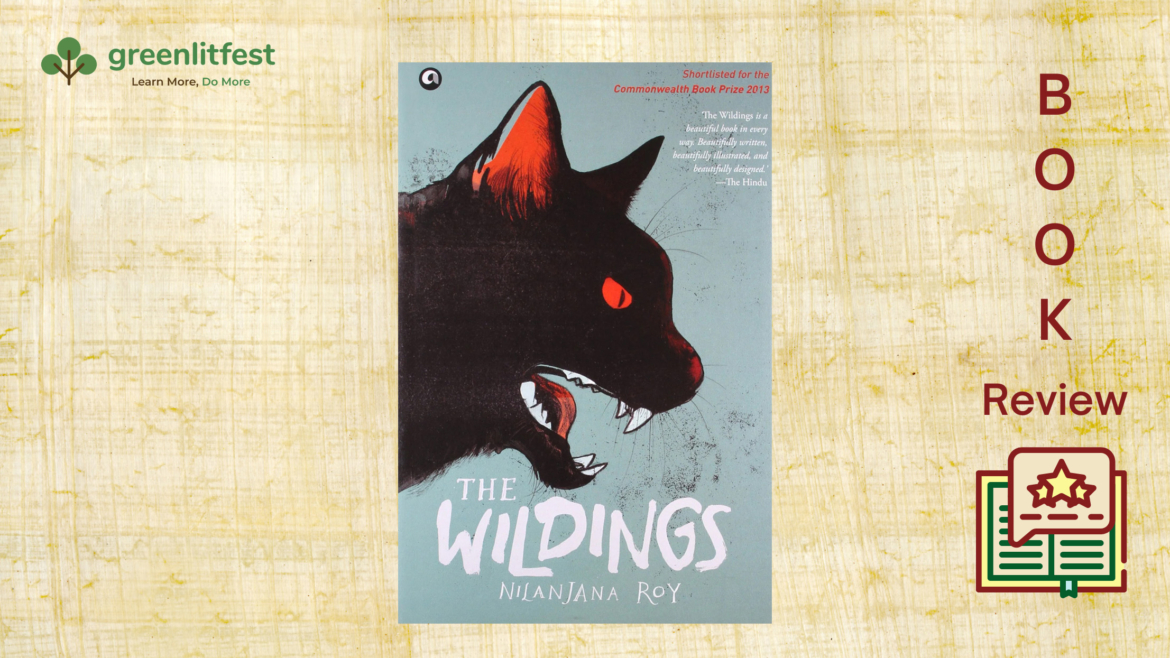

In a world dominated by humans, what happens to non-human species? From Rudyard Kipling’s The Jungle Book to Dr Suess’ The Lorax, this is a premise explored in some of the finest literature. Sometimes it’s seen through animal eyes and at other times, through human. Nilanjana Roy is very clearly a cat person and so, The Wildings explores the human-animal relationship through a richly-detailed cat-perspective with nary a false beat.

Stray animals make me nervous. But the novel made me set aside my fears and view the world from the eyes of animals negotiating their way through urban landscapes, where the rules of the jungle lie on thin ice. The strays abide by these as do the cheels, the mice and various other animal inhabitants of the neighbourhood. But the same cannot be said of animals bred in captivity – especially the feral cats closeted in the Shuttered House.

They think food comes from Bigfeet, and they only ever hunt old, lame rats or diseased beetles… living inside, shut up all the time, something warps in them. Their minds scurry in circles, like the grubs you’ve seen living under tree bark – here and there, here and there, never going anywhere. So, if their Bigfoot dies, they won’t have any food left after a while. And perhaps other Bigfeet won’t let them stay inside the Shuttered House… Then they’ll either break out and try to kill us, or turn on each other in a killing frenzy… says Miao, the oldest and wisest of the wildings.

The world may be divided into prey and predators, but even so, there are rules in this game and bloodlust is not one of them. However, deprived of their freedom by human patrons, the cats in the Shuttered House are outlaws. Yet, this is not a simple plot of villainous humans imprisoning animals and turning them into beasts. The aged Bigfoot in the Shuttered House is not a wicked old man, even though his dwelling is appallingly unhygienic and suffocating. The fakir at the dargah is trusted by all cats in Nizamuddin. As for Mara, she thinks her Bigfeet are ‘slow learners… resisting most of her efforts to train them’! If Bigfeet are not the villains, then who is? What is responsible for the deviousness of the ferals in the Shuttered House? Roy does not offer any easy answers. Instead, she invites readers to introspect – on ideas of freedom, deprivation and choice.

Her narrative has no human voices, yet the allegory is hard to miss. Clans, cat communities, the fear of ‘outsiders’, defining allies and enemies in the quest for self-preservation… it’s all there, moulded into beguiling prose. I doubt any reader of this text will be able to see the tabby cat in the same way again – and that’s a hallmark of great writing. It shifts our gaze and opens our eyes to possibilities arising from new ways of looking at the world. Humans may dominate the planet, but the world is a shared space.

Published by Aleph in 2012, the book is a fine addition to the body of literary fiction with anthropomorphised protagonists, such as Richard Adam’s Watership Down, Robert C. O’Brien’s Mrs. Frisby and the Rats of NIMH and S.F. Said’s Varjak Paw, that effectively use adventure and fantasy to comment upon the world. Comparisons, especially between Varjak Paw and The Wildings are inevitable, given their uncannily similar cat protagonists.

Although The Wildings has not been classified as juvenile fiction in India – quite honestly, I’m not a big fan of classifying books into juvenile and adult categories – it makes a wonderful read for all ages. I can well imagine it being narrated to little children in engrossing storytelling sessions spread over a few days. The fact that it has pictures by the adroit Prabha Mallya, known for her animal illustrations, only adds to its charms. So go ahead and fall headlong into this immersive world of cats in urban jungles as also in zoos!

Meghaa curates SN Youth and heads the Children and Youth programme at the Greenlitfest. She is currently completing MA in Environmental Humanities in the UK.