In our second pairing for the literary exchange, we look at elephant adventures featuring feisty girls.

Chaya, a no-nonsense, outspoken hero, leads her friends and a gorgeous elephant on a noisy, fraught, joyous adventure through the jungle where revolution is stirring and leeches lurk. Will stealing the queen’s jewels be the beginning or the end of everything for the intrepid gang?

On a holiday in the jungles of Kalagarh, situated along the periphery of the Corbett National Park in India, Gitanjali and her cousins experience elephant encounters of a very strange kind! A spine-tingling tale that is taut with mystery and tinged with humour.

Meet the Students

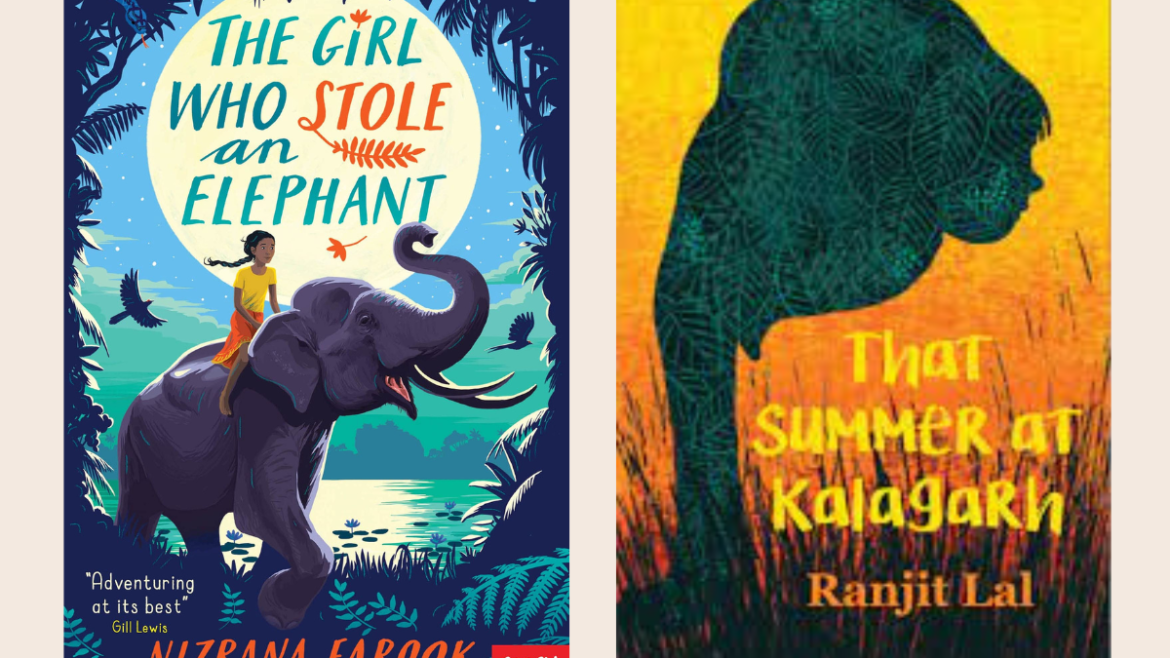

This month we have Zehra Naqvi from Ashoka joining Rebekah Curtis from Bath Spa for a conversation on our book pairing for the month: Nizrana Farook’s The Girl Who Stole an Elephant with Ranjit Lal’s That Summer at Kalagarh.

Zehra Naqvi has returned to student life after a decade of professional experience and is currently enrolled in the MA English programme at Ashoka University. She is an independent journalist and the author of The Reluctant Mother: A Story No One Wants To Tell.

Rebekah Curtis, studying on the MA Writing for Young People at Bath Spa University, writes middle-grade fiction and picture books with hopeful portrayals of nature.

The Discussion

Zehra and Rebekah speak about Ranjit Lal’s That Summer at Kalagarh and Nizrana Farook’s The Girl Who Stole an Elephant and how the books talk of wondrous ‘gentle giants’, drawing young readers into thrilling action-packed adventures, in a conversation with the Greenlitfest’s Meghaa Gupta.

Q. Was this the first time you were looking at writing for young people by an author from India/UK, and what were your first thoughts about the reading experience?

Rebekah: It was the first environmental book for children in India that I’d read. The environmental setting was really different from the UK, so it was really nice to immerse myself in it.

Zehra: We’ve all grown up reading Enid Blyton and there is quite a bit of the environment in there, because she is talking about parrots and butterflies and always describing different kinds of environments. But other than that I can’t remember reading any children’s books about the environment from writers based in the UK.

Q. Geographically, elephants are only found in parts of Asia and Africa. Yet, children’s literature in all parts of the world has a historic and abiding love for these creatures. Did you read elephant stories growing up? What were they all about, and why do you think they are a such a fixture in young people’s literature?

Rebekah: They are extraordinary animals, aren’t they! They’re this enormous land animal with a trunk and big ears that we would never see in the wild here. I think children’s books like all books need really strong characters and elephants make such powerful characters. Also, as a sort of metaphor for testing boundaries I think they’re a really interesting choice because they’re so friendly but also potentially dangerous and that’s a nice combination of character traits in them.

I’ve always had the Elmer books in my life. Elmer by David McKee is a patchwork elephant championing diversity and celebrating being different. The picture of the elephant, the colourful cloth squares like a quilt, just everyone knows it.

Zehra: Growing up in India, elephants have very much been a part of the folklore and the stories that we hear from our grandmothers and our mothers. Our family used to take trips to national parks and wildlife sanctuaries. By the time I was six I had already had elephant rides and my parents had their own stories of their journeys in national parks and how they took these elephant rides and what happened. Those stories are far more imprinted on my mind because they are real life stories of how they were on an elephant and they saw a tiger in the wild. We once had an elephant ride at the Amer Fort in Jaipur and the mahout asked me to extend my hand and the elephant actually shook it with its trunk. So more than stories from books, elephants have been a real part of my childhood.

Rebekah: I had the opposite experience because they just weren’t anywhere near here. I don’t remember seeing one in the zoo. They were so fascinating. I just wanted to see one, and books or the television were the only places we could see them. They were sort of incredible to me.

Zehra: For me, in India, it was more about the idea of a gentle giant. Like, here’s an animal that’s huge and it ought to be terrifying, but the kind of interaction we had with these elephants was actually very pleasant. So while we knew that wild elephants were to be feared, the kind of elephants we saw and interacted with were like these gentle giants. It was like having this giant, powerful but very gentle friend. A child’s dream come true.

Rebekah: That’s wonderful. Gentle giant is such a good description, I think, of how we perceive them in books, even though they can be really rough in the wild sometimes.

Q. Both the novels feature feisty young girls and their companionship with elephants. How convincing is this plot point and the story built around it?

Zehra: I found the way the book has been written really engrossing. It’s very fast paced, action packed. There is something happening every second. It’s like you blink and you will miss it. It’s so visually descriptive, it’s almost like watching a movie. And I was thinking that may be this should be adapted for the screen as a children’s movie. The kind of descriptions there are of the forests, the animals, village life and the girl, especially the things that she is doing, the ease with which she is outwitting an entire army of royal guards, it’s audacious! I was thrilled to read it and I felt like I had become a child again.

This is supposedly a 12-year-old girl and she is doing all kinds of things – stealing an elephant for heaven’s sake and riding it – but it’s written very convincingly that she used to watch the elephant keepers and how they were using these commands and learning through observation, she uses the same commands to move the elephant, make it bend. I was very happy to see such an action-oriented girl protagonist.

Rebekah: The Girl Who Stole An Elephant is such an active book. I completely agree. From the first line it’s exciting.

In That Summer at Kalagarh I found the bond between the girl and elephants really convincing. I just felt really invested in the character. I really liked Gitanjali and I think instantly there’s this connection between her and elephants. The way she moves, the sound she makes, the fact that she’s wearing a grey top, all these hints that she’s like an elephant and she’s compared to an elephant, and you start intertwining her in your mind with the world of the elephants. That link is woven in. Also, she’s a strong, likeable character, and when you care about the character you don’t question whether something’s convincing. You’re there, you’re interested.

Meghaa: I remember this scene in That Summer in Kalagarh where Gitanjali’s inside the park and the elephants are being violent and the others are scared but she isn’t…

Rebekah: Yeah, it’s a really powerful moment, because she’s this small girl and she’s got this power. And of course that’s one of those moments where you don’t think about whether you’re convinced or not. You’re there. You just want to know how! Why has she got this connection and how has she got this power?

Zehra: Agree with Rebekah. Sometimes you don’t really care about how convincing things are because you’re so wrapped up in the story. It’s an adventure story after all. We hear all these adventure stories about kids doing things that seem to be fantastical but you don’t doubt them because you’re so drawn into the story.

For me the prison break scene in The Girl… was one of the best parts of the book. It subverts the idea of who’s doing the saving and who is being saved. There is a young girl who’s breaking an older boy out of prison. It’s a reversal of roles from what we usually see, where it’s usually the girl being saved and the guy doing the saving.

Q. Do you think young people in your part of the world would be able to relate to these stories? Would they find anything unusual?

Rebekah: I think the bond between a child and an animal and connecting with nature is very universal. What was different was it’s not about a fox, a dog or a cat in the local park. It’s about the threat of tigers possibly being there. That’s really interesting. And I think, environmentally, it’s really important that children think beyond the boundaries of where they live, about the wider world. We share this world with many animals in different habitats, and I think it’s really important for children to think far and wide, and to travel through literature.

Zehra: The story in The Girl Who Stole An Elephant is quite culturally close to the kind of things we have in India. There’s a monastery, a temple, a king and village scenes – the kind of things that you could see in India. At the same time, you are also exposed to different things, like I had to look up to find out what a jambu fruit is because I had not heard of it. I showed the book to my son and he was very excited about reading it in his holidays.

It would be enjoyable for children because it’s so action-packed and adventurous and would hold the interest of children used to watching such things in the visual medium. It has a lot of animals making these cameos every now and then. There are leopards, water lizards, monkeys. The way that the elephant comes and rescues Chaya when she’s drowning. It has animals doing a lot of things. So I think that would be not just a learning experience but also a very thrilling experience for a child.

Rebekah: That’s a really important point about children watching television and film. The screen is so action-packed nowadays and the books need to keep up with this new, fast-paced world of television that we all have.

Meghaa: That Summer in Kalagarh is realist contemporary fiction, while The Girl Who Stole An Elephant is set in a place which has kings, queens, palaces and villages. I would be interested in knowing if either of you had any thoughts on whether such a treatment sometimes ends up exoticizing the east.

Rebekah: I think in general it’s really important for all writers to think about these things. When writers delve into creative worlds it’s always important to think about how elements could be perceived and how others may feel about it.

Zehra: I did not feel that at all, but I can understand why someone living in the west might feel like that because it depicts a completely different world, geographically and even culturally from what exists in the west. I found it more like historical children’s fiction, like this might not be the life that we are seeing right now but so much of it is resonant with the kind of life that we had not so very long ago. Even though it’s set in Sri Lanka, in India too we have palaces and our history is replete with kings and elephants and jungles. We do have all these stories and pictures of leopards and man-eaters. So I did not get the sense of exoticisation. I just felt that it’s set in an earlier time. I found it really refreshing to see a female protagonist and towards the end there is woman leading a revolution against a tyrant king. These are like bits of our history because obviously we’ve had female rulers in history, but these bits don’t get talked about so much.

It’s very interesting to have different perspectives about a book. I think there is a space for both kinds of books. We can have more realistic children’s literature like That Summer at Kalagarh but there is also space for fantasy. I mean where else if not children’s literature, because the imagination is such an important thing for a child. We are the land of elephants. I don’t know why we need to disown that. Let’s own it! We are a country where I as a child have shaken an elephant’s trunk. How many children would get to do that? We are a land of people who have seen snakes dancing. It’s true. So rather than seeing it as exoticisation, let’s own it as part of our history. There are multiple spatial and temporal realities to it. Isn’t it? So on the one hand we have all these sky scrapers and very cosmopolitan capital cities and on the other we have villages where you can still have monkeys in your courtyard. Just a decade or so ago, one of my aunts was drying her hair in the sun, in the courtyard of her home and a monkey just dropped in and started searching her head for lice! She was terrified, but this is the reality and there is beauty in it.

Meghaa: It’s happened to my mum right here in Delhi! Once when she was returning home with a bunch of bananas and milk, a tiny monkey came and very gently took them from her! There have also been monkey attacks, cases of monkeys stealing milk packets and getting into teasing matches with stray dogs in our colony.

Zehra: This is the reality. We are a land of animals and that’s what makes us special.

Q. Do you think the way these novels are being told relates to commonly held notions of environmental literature, and how do you think they contribute to one’s understanding of the Anthropocene?

Rebekah: I think the term environmental literature suggests the idea of serious storytelling, in a way, because it’s such a serious issue. But That Summer at Kalagarh just goes to show how environmental literature can be done in a really playful and adventurous way with lightness and humour. It reminds us that just because it’s a serious topic doesn’t mean you have to relate it in a serious way all the time. And it does deal with the seriousness of environmental issues as well. In this book there’s a lot of tension between humans and animals. There are the guards who fear the elephant, there’s the dam which floods the meadows and there are the boys who are always playing games centred around hunting. So you always feel this tension between humans and the natural world.

Zehra: It’s interesting that Rebekah talked about the tension between humans and the natural world. I wouldn’t say the natural world, because aren’t we also a part of the natural world?

It was surprising for me to have The Girl Who Stole An Elephant classified as environmental literature because I wouldn’t have thought of it as environmental literature. You have a certain idea of environmental literature being something that is, for the lack of a better word, more activist in nature. Something like, for example, The Great Derangement or something that talks about how humans are impacting the environment, or climate change. But to classify this book as environmental literature expands the definition of environmental literature. It makes it that much more interesting, particularly for children, rather than just a sort of doomsday prophecy.

I would like children to grow up with hope. I mean who else would have hope if not kids, if not the younger generation. What I really liked about this book is the everydayness with which it speaks of the jungles and the creatures in the jungle. There is the difference between Chaya, who is clambering around, doing all these activities and her friend Noor, a Muslim character whose her family has migrated from a place which is supposedly a desert. Noor is new to these surroundings and because she comes from a very privileged background, she brings bed sheets and candies as supplies for going into the jungle! It’s a very tongue-in-cheek comment about how people who are living with certain kinds of privilege have become detached from the environment and have begun to fear it, as compared to people who are living in less privileged surroundings and have the everydayness of the environment in their lives. They do not treat it as something to be feared. They have learnt to coexist. So when a leopard appears in front of them, Chaya and her friend Neel are scared but they know how to deal with it. They know how to behave. They know you have to be very still and not make any instant action, and they behave in a normal way when they have leeches stuck to their body, whereas this girl from a privileged family is screaming. She is terrified and honestly I would be terrified as well, but these kids are okay to let the leeches suck their blood and fall off when they’re full because they don’t have any salt to sprinkle on them! I was astounded at this description. This sort of mundane way of looking at something like a leech that is stuck to your skin and is sucking your blood is a kind of lesson in how you can coexist with other creatures and how people who’ve become accustomed to living in privilege and protected environments look at other creatures with fear, as things that they cannot deal with. This book conveys it fabulously, without being didactic.

Q. Book recommendations from your countries that you think that others in other geographies should know about.

Zehra:

Tigers for Dinner: Tall Tales by Jim Corbett’s Khansama by Ruskin Bond

It’s a very interesting and exciting book about living in the jungle and having tigers pay you a visit there!

Cricket for the Crocodile by Ruskin Bond

It’s about a crocodile which lives by the riverbank, where some kids play cricket every day, and how their ball gets stuck on the crocodile’s body. So it unwittingly becomes a part of the game.

The Jungle Radio: Bird Songs of India by Devangana Dash

It’s an illustrated book about the sounds of birds in India.

Rebekah:

Melt by Ele Fountain and The Last Bear by Hannah Gold

Both these books deal with the issue of Arctic ice melting

Otters’ Moon by Susanna Bailey

It’s a really tender story about a boy’s friendship with an otter and it deals with plastic pollution in the sea.

The Book of Hopes: Words and Pictures to Comfort, Inspire and Entertain Children in Lockdown, edited by Katherine Rundell.

It’s a collection of hopeful writing by authors and it has some pieces based on nature. It’s a really lovely collection.