In our fourth and final pairing for the literary exchange, we look at the human relationship with land and how childhood is placed within it.

Dylan’s mum thinks he’s on the school Geography trip. Dylan’s teacher thinks he’s at home with the flu. In fact, he’s 30,000 feet up in the air on his way to Brazil. When Dylan’s farm is snatched away by a huge global company, he can’t just sit back and watch. But the journey to rescue his home takes him deep into the heart of the Amazon. With Floyd, a friend he’s not sure of, and Lucia, a street kid armed with a thesaurus and a Great Dane puppy, he uncovers dark and dangerous secrets, and learns some surprising truths.

Korok lives in a small Gond village in western Odisha. His life is in the garden which he tends every day. Anchita lives in the house which has the garden and is an artist. One day, the government tells the Gonds they have to leave the village because a company is going to mine the sacred hill next to it for aluminium ore. The Gonds oppose it, but the mighty government, led by police officer Sorkari Patnaik is determined to win. What can a lone gardener and a girl with a computer do against the most powerful people in the land?

Meet the Students

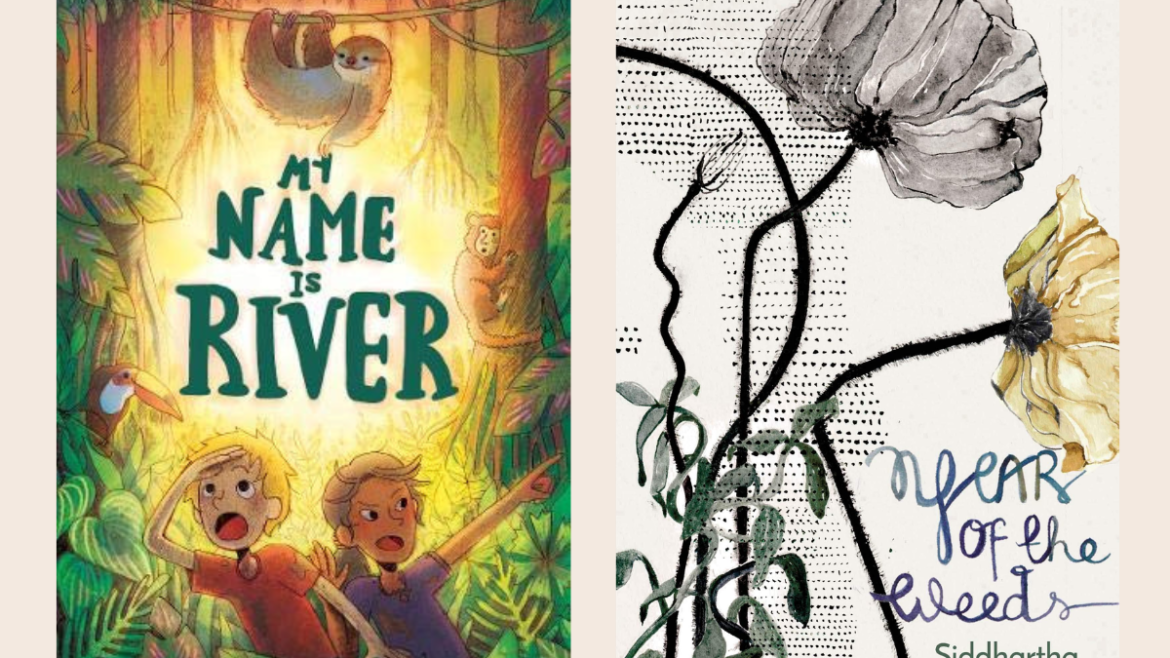

This month we have Pooja Kadaboina from Ashoka University and Rupert Barrington and Janette Taylor from Bath Spa University speak about our book pairing for the month: Emma Rea’s My Name is River and Siddhartha Sarma’s Year of the Weeds.

Rupert Barrington works for the BBC, making wildlife documentaries. He is currently taking the MA in Writing for Young People at Bath Spa University.

Janette Taylor studied Biochemistry before training as a primary school teacher. After teaching for many years, she decided to devote more time to her passion for writing.

Pooja Kadaboina is a graduate student of English literature at Ashoka University. She takes a particular delight in framing a dialogue between questions of children’s literature and queer theory.

The Discussion

Pooja Kadaboina from Ashoka University and Rupert Barrington and Janette Taylor from Bath Spa University speak about Siddhartha Sarma’s Year of the Weeds and Emma Rea’s My Name is River. They ponder over the complex human relationship with land and placing the world of childhood within it, in a conversation with the Greenlitfest’s Meghaa Gupta.

Q. Was this the first time you were looking at writing for young people by an author from India/UK, and what were your first thoughts about the reading experience?

Pooja: My studies have largely focused on children’s literature, so it wasn’t the first time I’ve come across a book written by an author from the UK. My first point of reference, especially because of my thesis, is folklore and fairy tales, particularly the tradition of rewriting fairy tales by authors like Angela Carter. Carter’s rewritten fairy tales are quite the radical read for young people who grew up in the familiarity of popular fairy tales. It’s really interesting to look at why we keep going back to popular narratives that we hear as children and why it’s so important for us to go back to these narratives and pick apart elements to see where each element can lead us to, in that story.

Rupert: I think probably only one, A Cloud called Bhura by Bijal Vachcharajani, which I thought was brilliant.

Meghaa: How did you get your hands upon this book?

Rupert: I read a newspaper review about how this book was an example of how to write entertaining climate fiction for children. So I thought it was a book I needed to read and ordered it off the internet. I thought it was very funny. It absolutely got the kids’ point of view, while dealing with very big issues. It was very realistic about what kids can do about climate-related problems.

Janette: Year of the Weeds was the first book that I’ve knowingly read, by an Indian author for an Indian audience.

Q. Both the books offer powerful narratives on the sense of belonging to land. Did they make you ponder about ways in which people in different parts of the world connect to land and how similar or different this may be to your own experience of landscape?

Janette: I think in Britain the connection to land tends to be more ancestral, you know, if your family have lived in a place for a long time, but I think people are moving around so much now I don’t think there even is that connection for a lot of people. I wouldn’t say that I feel that I belong anywhere or that I have a particular place that I’m connected to. I think what struck me so much about the Year of the Weeds is that it wasn’t just cultural, but it was a sacred connection to the land and I think that’s something that we don’t have so much here. It just tends to be that my family have lived here for a long time.

Rupert: I’d agree with what Jeanette said exactly. I think we don’t have the same level of spiritual connection with the land that we read about in this book. One of the things I try to do in my job is to help people form more of a connection with the natural world. That’s what we make our wildlife programs at the BBC for, but it’s a very different thing having that on TV to actually feeling something emotional towards the landscape and the biodiversity that lives in it. So I found this fascinating because it’s not a mindset and a connection that we really have to deal with here. It’s something much deeper than the vast majority of this country would feel for the land.

Pooja: I’m probably more used to the vocabulary of the land and the relationship with it being more spiritual, but what I found refreshing in My Name is River was the sentiment of perceiving every other natural being around you as an active agent that’s a part of the environment that you inhabit. It puts aside things like power, when you look at all elements as active agents playing their own part.

I think, in India, aside from land being tied to ancestry and power, landscapes convert to the experience of climate and the weather. Having moved across geographies within the country, I realise how extreme and variable temperatures can get. I’ve experienced summer here at Ashoka differently this year and last year. There is more rainfall this year. So I think the climatic changes become more visible here as you move across terrains and you begin to see how that dictates the ordinary experience and the cultural idiosyncrasies.

Q. Human connections to land are multi-layered and complex, laced with a multitude of social, cultural, political and economic nuances. How convincingly do the novels place the world of childhood – the stories of Korok and Dylan – within this complicated reality? Did you ever get a sense of suspension of disbelief while reading the stories?

Rupert: Year of the Weeds, I thought, placed the child Korok very well in that world and I never had to think that I was being told a story. It was very involving right from the beginning. I understood where he was and what his relationship with that land was. It was done in a very natural way. I also thought his relationship with the wider world of India and his beginning to understand the whole politics of India and how that was impacting his people was beautifully done and very organic. I felt he was learning that very naturally through what was happening to him. I was completely in his point of view right from the beginning.

Janette: Yeah, I was totally immersed in his world and it was very vivid. I believed everything about it. I think, the one thing I would say, is it didn’t feel very much like a childhood. Korok didn’t feel like a young person to me in a lot of ways because he was so independent and I think his life was very different from that of a British teenager. It made his interests very different to a British teenager. For example, for a teenager here everything is so much about social media. It’s a very technological life, so the simplicity of Korok’s life made him feel very different to me. I found it refreshing, but I also found it very interesting because the things that mark out a young person’s life here were very absent from his life.

Meghaa: This is a young adult novel based on a real people’s movement that happened in India and Korok is a young person whose childhood has been stolen from him because of the very repressive social reality in which he finds himself. I’m wondering how privilege plays into shaping childhood and our ideas of childhood, and what an underprivileged childhood in Britain looks like.

Janette: I don’t mean that Korok didn’t feel real to me, but I think it just struck me that he was a young person having to live a very adult life because he was having to take care of himself, feed himself, he was visiting his father in jail. He had all the responsibility of an adult. He was working. He was gardening, tending plants all day, and I think in Britain even people who are comparatively poor and underprivileged would have access to technology, even if it was only in the school context, and there is a big move to hand on second hand laptops to people and those kinds of thing. So, I was just very struck by the difference and how adult he had to be for someone who was so young.

Rupert: I think one word you mentioned was education. Korok had no education to speak of, and generally in our country even underprivileged people have access to some kind of education. You don’t know how good quality that’s going to be, how long they’ll stay in that system, but it’s there, whereas clearly Korok’s opportunities for education ended when the teacher left the school. He was clearly drawn to be a bright boy, who was probably never going to get those opportunities. But you saw in the story, another character from the Gond community who had had an education and what a difference that made to them that one person understood what they were up against. So you see beautifully in the story what not having a proper education can deny a child.

Janette: I actually taught in a comparatively underprivileged area up in Hull and all the children had access to technology.

Meghaa: I’m just dwelling on this a bit more, but is there some way privilege factors into our relationship with the environment because both these novels do include that in their many layers?

Janette: For Dylan, in My Name is River, initially at least, the farm is where he’s always lived, his family have always lived and what he perceives as his future. It’s about fun. It’s his tree house. It’s the log where he sits. It’s a place to play, whereas to Korok it’s a place of work and it’s a sacred place. It’s not got the same sense of fun about it.

Rupert: I’m not sure that privilege necessarily has an impact on your relationship with the natural world. At one level, where you live, does. If you live in a city and don’t have opportunities very often to get out to the countryside, then you will probably not have the opportunity to build a relationship with the environment. But whether you are underprivileged or wealthy, living in the countryside does not automatically mean you form a strong connection with the environment. I think in the UK we face a cultural problem with the environment, which is that a proper interest in, and connection with, nature is not something that runs deep anymore.

Janette: I think some of that may be around the availability of technology, because if children didn’t have that technology they would entertain themselves outside.

Rupert: Yeah, that may well be true.

Meghaa: That’s a whole different discussion but it’s an interesting point.

Pooja: I think Dylan’s childhood in My Name is River portrays a possible loss of an adulthood, a future that Dylan imagined for himself – that he wanted to grow up to be a farmer, tend to the land, grow old on his farm, surrounded by sheep. Emma Rea shows you how in tune he is to the place that he’s grown up in, and he’d like to grow up with rather than grow up in this place.

I’m not sure there is any suspension of disbelief. What Janette said about the protagonist not seeming like a child, caught my ear. I think Dylan has this resolute character, which allows you to put aside the fact that the adventure these kids get into might be dangerous, something that they might not even be able to get into otherwise, because adults won’t take them seriously. And I think that’s a thing that the book sort of turns on its head, because the adults actually listen to what these children have to say.

Q. Do you think young people in your part of the world would be able to relate to these stories? Would they find anything unusual?

Rupert: I think they would be able to relate, but it wouldn’t be something that they would instantly recognise for the reasons we discussed earlier, about the fact that we don’t have the same sort of relationship with the land. I think it’s something they would need to develop an understanding for as they read the story. Also the fact that Korok, as we talked about, is quite old for his years. He’s had to grow up fast because of the responsibility on his shoulders and that is something that children here tend not to have to do. So I think there are a few steps children will have to take, to put themselves in his shoes. But I think once they’ve done it, the story is so well written, the characters are so vivid, and the struggle of the Gonds is so well told and uplifting at the end, I think children would like it. It’s a YA book and I think that would be right for the reading age here as well.

Janette: I think Korok’s childhood is very different to the life of a young person here in the UK, but then young people read books about children in totally fictional contexts, in fantasy or in other contexts, and they can get into a character whose experience of life is very different to theirs. So I don’t see why they wouldn’t, in this case. Year of the Weeds is a beautifully written book and I enjoyed reading it immensely. There is so much that they could get out of reading it. It’s a different view of life. So I think if they would give it the time they would reap enormous benefits from reading it.

Meghaa: We keep talking about people wanting to see themselves in the books that they read and, in that sense, what you say about young readers having to struggle a bit to get into the narrative of Year of the Weeds probably doesn’t make it a natural or even as easy choice.

Janette: I think the pace of the book is very gentle and, I might be wrong, but teenagers are perhaps a little bit lacking in patience and want a more instant reward when they’re getting into a book. Still, I think it’s a good pace because it allows you to really sink into the environment and the culture, and as an adult reader, I thought that was lovely. I think they would get a lot from it if they did read it. I think it would challenge them about their own values, what matters to them, and I think the ending is so satisfying. The part when Patnaik got his comeuppance was wonderful and I think young people would really enjoy that.

Rupert: I was just going to add to what Janette was saying. I think it’s probably a book that children would need to have recommended to them by teachers or a parent rather than one they’re going to pick off the shelves by themselves. I quite agree that if they get into it, there’s a lot for them to take. A lot of enjoyment, a lot of fresh understanding.

Pooja: I think My Name is River would be immensely relatable. It has a really large theme that unravels throughout the narrative, that everywhere in the world is the same, but at the same time it’s not-so-same after all. There are some differences, but that doesn’t mean you’re always going to end up in an environment that will be entirely unfamiliar to you. It’s got an interesting mix of protagonists – Dylan’s from Wales and then you have Lucia from Brazil. She’s a bold character. She’s curious and she’s as nifty as Dylan, if not more, because of the cultural and socio-economic background that she comes from. She recognises the very real threat of impoverishment when it comes to literacy, if she doesn’t keep her curiosity up. Both Dylan and Lucia provide different models of relatability. With Dylan you see the kind of child who understands that plans always change and that this is all right and you just have to navigate what’s in front of you at the moment. At the same time, he is also a child who doesn’t know what to do and would like to believe that if you turn to any adult, they’ll sort of make the world right for you. Even the whole thing about being able to see what runs in someone’s veins becomes a metaphor for just listening to the way that you respond to things, the sort of answers that come to you, and not dismissing yourself as a child. With Lucia, you have her overcoming her circumstances, wanting to learn as much as she can and going for what she wants despite being from the circumstances that she is from. So I think there is so much that is relatable here about these characters, and even more than relatable, it is reaffirming for steering one’s own circumstances.

Q. Do you think the way these novels are being told relates to commonly held notions of environmental literature, and how do you think they contribute to one’s understanding of the Anthropocene?

Janette: Although the main theme in Year of the Weeds is centred more around the community being displaced and loss of the Sacred Hill, it is all about how the big companies and the government are valuing the resources they can grab out of the earth rather than the forest that’s growing on it and how little they respect the natural world compared to the resources that it can provide them with.

Rupert: I would agree with that. Year of the Weeds is not a book about the natural environment and biodiversity. It is about a clash of cultures, or privilege against underprivilege. I think what it does brilliantly, which for me makes it environmental literature, is it sort of shows the root cause of so many of the problems, which is greed, which is insensitivity to people who can’t, for whatever reason, fight for themselves and the places where they live. It offers hope, a solution in the end that is uplifting. It shows that all is not doom and gloom, and I feel that’s a really important thing to offer children.

Meghaa: I’m interested in understanding if what you’re trying to say is that often times what we quote as environmental literature is essentially narratives of natural history and biodiversity and not so much of cultural history and society.

Rupert: This feels much more a book about society rather than about nature, if you see what I mean, but it’s about society as it impinges on nature. I think the focus is quite different in this to something in which the focus is on losing polar bears, for example. This is about the secondary effect of these imbalances in society on the natural world.

Janette: For my essay I’ve been looking into climate fiction. The books are mostly about the damage to the planet and how we save the planet and how we save the species – the polar bears, the whales, the everything. So I think it doesn’t fit into that category, as such. I think it is very much about the impact we have on the natural world, but in a less overt way.

Meghaa: Environmental books tend to foreground the environment and background the human involvement in it, but we are living in an age where human activities are transforming the planet in such profound ways, maybe one needs more literature that foregrounds both of those things rather than one of those elements. Since you wrote an essay on climate change books for children, would you agree to this, Janette?

Janette: What I was really looking at, in my essay, was the benefits of using fiction as opposed to non-fiction to educate children about climate change and the impact that we’re having on the environment.

Rupert: I think all the points you’ve made are very good points – that the environment does not exist in isolation from humanity and it’s that interaction where the problems arise. So yes, maybe there is some middle ground which isn’t that well-trodden yet, between books on society and books on the natural world and maybe more literature in there would be very effective.

Janette: One of the books that I was using for my essay was The Lost Whale by Hannah Gold. It shows the effect of human activity on the oceans in a very good way. You’ve got a very good story there.

Meghaa: I think fiction probably won’t exist if you don’t have humanity in it, but there is definitely something to be said about addressing those dichotomies in non-fiction for children.

Pooja: My Name is River is pretty on-the-nose about the environmental issues that it tackles. Throughout the book you realise that the kind of metaphors Dylan uses, have all got to do with the natural world that he has seen around him. The activities that he is engaged in, that sort of an idyllic agricultural life, become the framework of his story. He is aware of every blade of grass that takes up space around him, not just at home, but even when he is landing in Brazil. Once he sees the blades of grass at the landing, he feels grounded after being airborne for so long.

Alongside the anxiety and fear of flying, there is also this very sweet realization that plays out when he is actually flying over the sea. He realises it’s a new environment, a new ecosystem of animals, that he is flying over and that becomes a grounding element.

I also have to circle back to your point, Meghaa, about there being a dichotomy between what we say are stories of the natural environment and what we say are stories of the human environment that don’t have to include nature, because what this book also shows is that sometimes stories on the environment are stories of poverty. They are stories of capitalism, and in India they are stories of caste. So these are different ways in which human beings not only engage with each other, but also have an impact upon the environment.

Q. Book recommendations from your countries that you think that others in other geographies should know about.

Rupert: Where the World Turns Wild by Nicola Penfold is brilliant because it’s written with such a respect for nature as something which isn’t just a commodity to be used, but has a value in its own right. It’s rich and it’s potentially dangerous and it contains everything that humanity needs physically and mentally, to live a good life.

Journey to the River Sea by Eva Ibbotson is one of the best love letters the environment I’ve read. It’s a beautiful exploration of what nature and all its diversity does to people who are receptive to their connection with the world. The way she takes her character into the Amazon, the way her character falls in love with everything about the Amazon – the climate, the plants, the animals and people – is wonderful.

Janette: I’m going to go with two and you’ll notice a slight theme here. So I’m going to recommend The Lost Whale by Hannah Gold, not to be confused with The Last Whale by Chris Vick. I like how Chris Vick really leans into the importance of the whale in the ecosystem. In his words, save the whales, save the planet, because of the amount of carbon that whales are able to absorb, comes across really well.

I absolutely love Hannah Gold’s The Lost Whale. There’s one part where the protagonist falls into the ocean and comes face to face with the whale and it nudges him back to the boat and you think, in that moment, of how intelligent and magnificent these creatures are, and then later we see the same whale caught in plastic and that just brings such an emotional connection to the damage that’s being done.

Meghaa: It’s interesting that both your books are about whales because I think most of us will spend all our lives never having seen a whale, so fiction is probably the only gateway to really understand that life.

Pooja: I wanted to recommend two books by the Nepali author and artist, Ubahang Nembang. The Journey and The Visitors. The Journey is based in a forest around the Panchase village in Nepal and tells the story of a water buffalo making its way back to the village where it’s fed salt by a boy sitting under a tree. It’s a metaphorical look into everything that the region has lost including its buffalo herding tradition. The Visitors is a mix of myth and reality and speaks of visitors from the forest to the city and how their presence turns the cityscape into a wild space.

Tiger on a Tree by Anushka Ravi Shankar is another obvious pick that plays with words and images.

The Honey Hunter by Karthika Nair is about a little boy who collects honey. It delves into a popular myth of the Sundarbans.