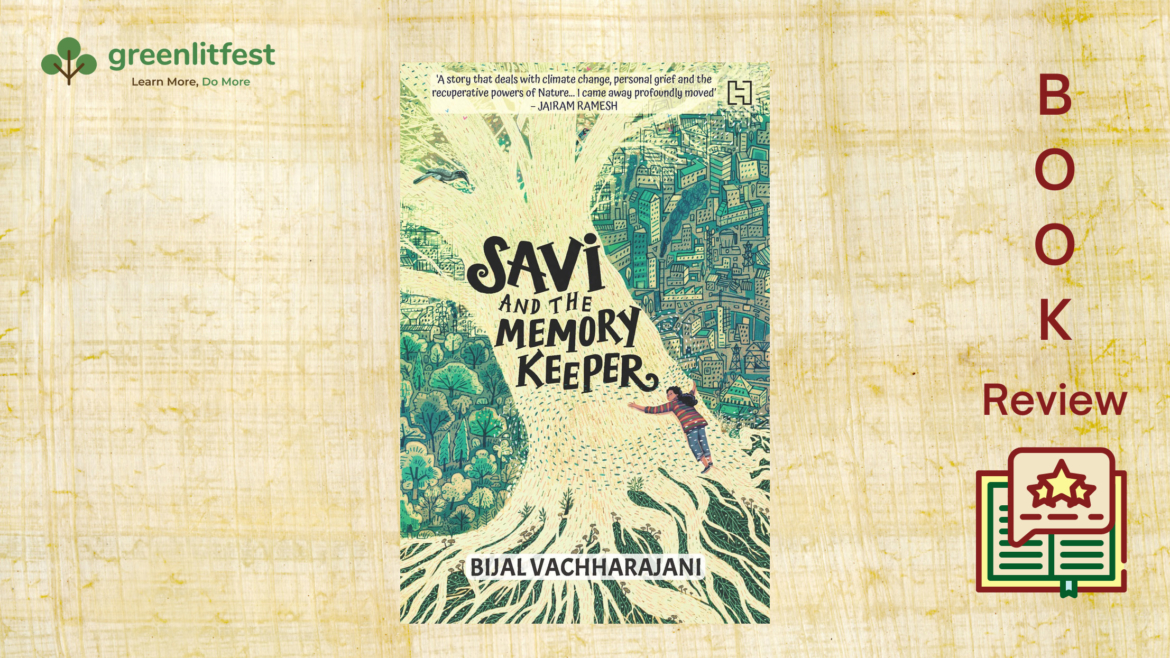

An intimate tale of of the human-nature relationship that is often lost in larger conversations around the exploitation of the Earth’s resources.

Straddling the dichotomy of Progress versus Nature is the fictitious city of Shajarpur, marked by a sense of joy, peace and calm that’s borne out a healthy ecosystem of flora, fauna and humanity. But it seems Progress, represented by powerful Uncles and (two) Aunties, is gaining ground. An insidious attempt is being made to uproot the Wood Wide Web – an underground ecosystem of roots, fungi and bacteria that form a network amongst the trees of the area. When it seems like Shajarpur will fall victim to climate change and the demands of industrial development, in walks Savitri, a.k.a Savi, an initially unwilling and cynical hero.

Bijal Vachharajani’s Savi and the Memory Keeper tells the story of a young girl in middle school who is dealing with the sudden loss of her beloved father. Her suffering is made worse, when she has to move from dreary, smog-filled Delhi to Shajarpur – her father’s green, bright, unbearably happy hometown.

In an attempt to forget her loss, Savi’s mother distracts herself by obsessively cleaning, to the point that she almost transcends reality. Her Insta-obsessed older sister, Meher, seems to have everything in control, with her beauty, charm and social media followers. Meanwhile, Savi feels alone, stuck with caring for her father’s potted plants and petrified of classmates at her elite new school.

Savi’s life is moving on, without her permission. She finds herself snapping at people without meaning to and is unable to comprehend, let alone express, what she’s going through. This is a situation, I’m all too familiar with. A few years ago, I too lost my father. Like Savi, I am the younger sibling and haven’t figured out what to do with grief. The book captures just how unknowable, overwhelming and frustrating grief is. How it takes over our will and lords over our lives. Dealing with grief requires wresting back control.

In the midst of this chaos, Savi finds the tree on the school grounds and the plants at home speaking to her and showing her memories – of Shajarpur and her father. This becomes an unlikely source of comfort and Savi ends up developing a deep relationship with nature around her. So, as the happy ecosystem of Shajarpur turns darker and the effects of climate change materialise, she steps in for a fight to protect it against the perils of Progress.

Vachharajani takes on a personal perspective when it comes to the environment discourse. Through the storylines of the protagonist, fellow classmates, teachers and her late father, the author reveals the intimacy of the human-nature relationship that is often lost in larger conversations around the exploitation of the Earth’s resources. One finds tenderness, care and companionship in engagements with plants and animals, big and small. The destructive forces of economic development crush such relationships. The scent of freshly minted money, the prospects of material life (consumerism/capitalism) and what Marx calls the ‘false consciousness’ make people forget this love of the green universe. Our world today distances humanity from nature, making the latter a thing that must be dominated. But what we don’t realise is that we aren’t winning. The few who do feel like they are winning may have an abundance of cultural and material power, but this blinds them to destruction that may prove to be fatal to all life on earth.

Indigenous people’s loss of land, class differences, bullying, celebrity culture, superficiality… the book often branches off into a multiplicity of directions. Coupled with several jumps in the timeline, this sometimes makes the narrative difficult to locate, even though the entire story is told from Savi’s perspective. Major plot points are packed into the last few chapters, leaving one to ponder over questions such as ‘Why did an uncle and aunty suddenly join the environmentalists?’ We are left to presume that there must be some good in the bad, some conscience among the unconscionable. References to Beyonce’s hit from over a decade ago, Ryan Gosling and Mondrian paintings, make the protagonist sound much older than an average twelve-thirteen-year-old. In fact, there is an uncharacteristic maturity to the characters in this book, who appear closer to millennials than tweens yet to enter high school.

Vachharajani’s strength is her ability to tell a story of human emotions. It is easy to relate to Savi’s dilemmas, her journey to finding inner courage and her fear of forgetting her father. This made me wonder if the book would have worked better as a diary. The format might have addressed some of the concerns arising out of the first-person narrative.

Climate fiction is an emerging genre in India and Vachharajani is undoubtedly one of its strongest proponents. Where Savi and the Memory Keeper succeeds is in its ability to introduce drama into what is otherwise seen as essential non-fiction for children growing up in a world beset by climate change. This makes the story come alive almost in the fashion of a film and is sure to find several readers looking for books that address vital dimensions of life enveloped in an ethereal web of nature.

By Naina A