By Anil Menon

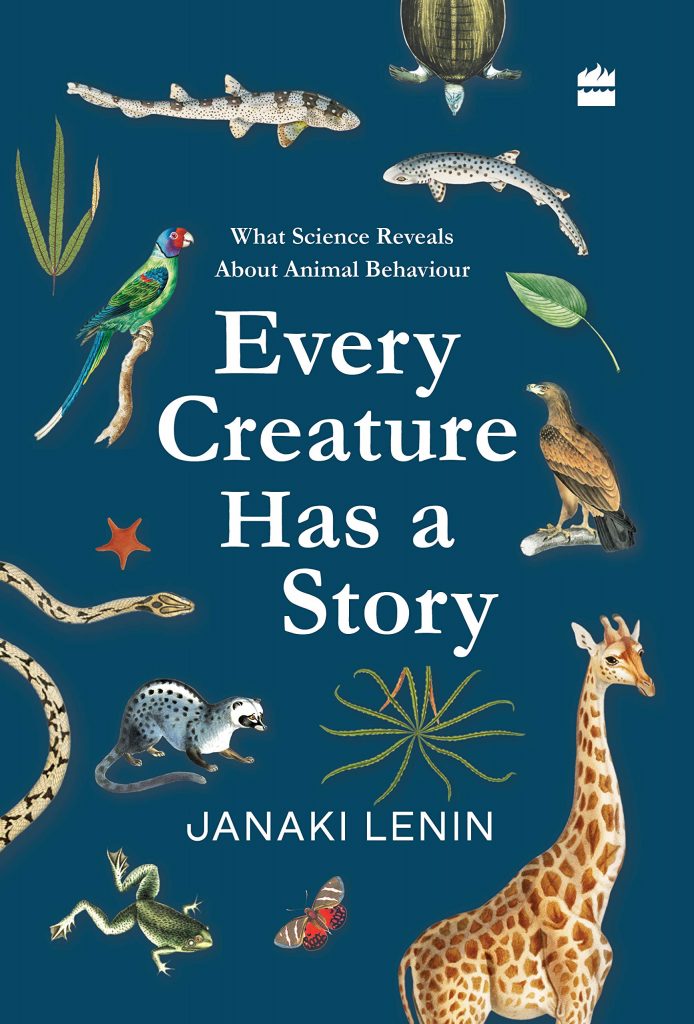

Janaki Lenin’s collection of essays Every Creature Has a Story: What Science Reveals About Animal Behaviour is a welcome addition to the rather sparse library of works by Indian authors with the aim of popularizing science. In this case, each short essay explores the intriguing evolutionary adaptations of popular and not-so-popular critters of the animal kingdom. Thus we learn about whether chimps grieve over the loss of their loved ones (spoiler: they do); why elephants are less prone to cancer (spoiler: a magic gene); and how mosquitofish have sex (spoiler: males aren’t picky); and what bees do to get vaccinated against germs (spoiler: they feed their queen).

In collections of this sort, perhaps the great difficulty is to figure out just how much readers know. After all, most of us have binge-watched nature documentaries. We all have that knowledgeable friend who feels compelled to inform us, over dinner, that according to Scientific American, Great Tits are “murderous, rapacious, flesh-rending predators”. Didn’t we all become expert epidemiologists during the COVID years?

Janaki Lenin seems to have settled on the idea of a reader who is perhaps a lot like herself: curious about the world, not a professional biologist, and having just enough understanding of biology to follow explanations that involve genes, immune responses, evolutionary strategies, and the consequences of global warming.

Except for an essay on the poisoners of the living world, the nightshade plant, the other essays are non-vegetarian, so to speak. By and large, the critters are of a size that wouldn’t require a microscope to see them. They can slither, bite, sting, trumpet, dash, bark and swim. The essays aren’t organized in any particular order.

The chapter titles are wonderfully irreverent and intriguing, but I felt the writing that followed didn’t do justice to either the title or the creature being discussed. For example, the chapter on “The Oddest Bird in the World” turned out to be about the kiwi, and we learn that its nasal receptors lie at the end of its beak. Sure, that’s marginally odd (the beak is a kind of nose, isn’t it?), but does that qualify the kiwi as the oddest bird? Or take the chapter “Sex Change in Bearded Dragons”. That’s a dynamite title. But the text that follows is a droning explanation about gender-control via temperature and genetics, and which boils down to the flamboyant “chaotician” Ian Malcolm’s remark in Jurassic Park: “life finds a way”. It made me wonder, again, about the book’s intended audience. The material is too sober for kids and adult readers will probably be turned off by the somewhat classroom-lecture feel of the essays.

The book’s title tells us that every creature has a story. It’s the “story-ness” which is missing. The scientists are presented as objective beings, inexorably adding one brick after another to the wall of science. But the ones I’ve met are less simple: they’ve been creepy, biased, dedicated, stupid, conniving, brilliant, generous and complicated.

Science needs to be humanized. This book is a useful addition to the literature of popular science, but I got the sense Janaki Lenin’s best effort is yet to come.

Anil Menon is the chief editor of The Bombay Literary Magazine. His books include The Coincidence Plot (Simon & Schuster, 2023), The Inconceivable Idea of the Sun: Stories (Hachette, 2022), Half of What I Say (Bloomsbury, 2015, shortlisted for the 2016 Hindu Literary Prize), and The Beast With Nine Billion Feet (Zubaan, 2009, shortlisted for the 2009 Crossword Prize and the Carl Baxter Society’s Parallax Award).