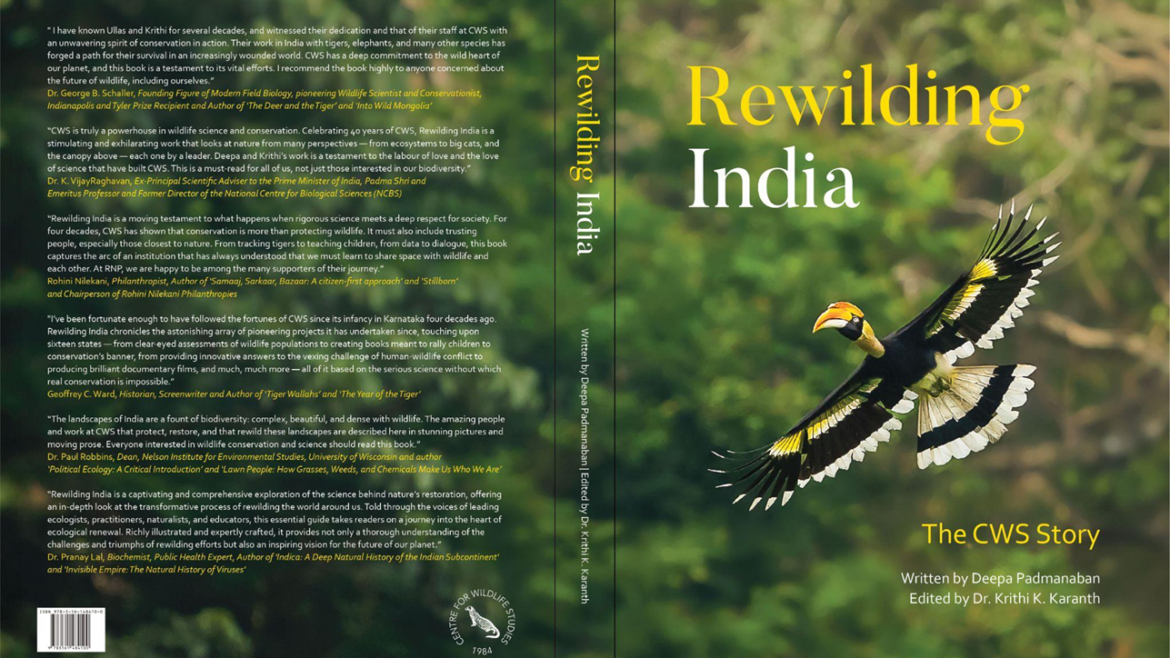

With a many-angled approach to nature, Rewilding India: The CWS Story addresses themes such as ecology, along with details of monitoring tigers, elephants, herbivores, primates, and the impact of wildlife tourism. It also brings to light infrastructure development on wildlife, human-wildlife conflict, illegal trade and hunting, as well as conservation programs for conflict and environmental education.

An excerpt from the book

As the first rays of dawn painted the sky with hues of pink and gold, a majestic herd of elephants emerged from the mist-shrouded forests of Nagarahole. These gentle giants moved with a rhythmic grace that belied their immense size. With a few playful young ones in tow, the elephants crossed the babbling riverbanks and traversed fields of emerald green. Sometimes, the elephants would pause at a banana farm, their keen senses drawn to the tantalizing aroma of ripening fruits, which they would devour with relish. Other times, the herd would simply continue their trek, their forms gradually disappearing into the dense foliage of the forest, leaving behind a trail of wonder and awe.

India, a land steeped in tradition and biodiversity, has long been home to the majestic Asian elephant. From ancient scriptures to royal processions, elephants have held a revered position. During the reign of Emperor Jahangir in 17th century India, his army was said to have had 1,13,000 captive Asian elephants (S.S. Bist et al., 2002). This points to the abundance of wild elephants that roamed the country back then. Unfortunately, in the last few centuries, elephants were poached for their ivory and forests cut down for farming and industry, and that led to habitat loss and increased human-elephant conflict. As a result, their populations underwent a drastic decline. The Asian elephant is now listed as endangered, with fewer than 50,000 individuals estimated to survive in Asia (Williams et al., 2020).

The Asian elephant is currently found in 13 countries across the Indian subcontinent, and Southeast Asia. India still remains a vital refuge for nearly 60% of the world’s wild Asian elephants (Pandey et al., 2024). But these gentle giants are under siege, largely restricted within protected areas that are often fragmented by human encroachment. Recognizing this urgent crisis, Project Elephant was established in 1992 by the Government of India to protect the Indian elephant and its habitat. While this initiative has boosted conservation efforts, there were still significant gaps in understanding and monitoring elephant populations. Earlier methods such as ‘waterhole’ and ‘block’ count censuses were deemed unscientific and unreliable by India’s Elephant Task Force in 2010.

CWS scientists led by Dr. K. Ullas Karanth have been at the forefront of elephant conservation since the 1980s. Through tireless research, they developed reliable methods to track and estimate elephant populations. For wider dissemination of this knowledge, CWS also partnered with several scientists to conduct a technical workshop, held in India’s Nagarahole reserve in 2003. It focused on rigorous methods for estimating elephant populations and assessing threats to their habitat. The outcome was an open-source manual, “Monitoring Elephant Populations and Assessing Threats,” that has become a valuable resource for conservationists worldwide.

To mitigate increasing human-elephant conflict, CWS has also actively engaged in understanding these complex, ever-shifting interactions across different landscapes.

Where Are the Elephants Present? Estimating Distribution Using Occupancy Sampling

The first question that arises in conservation is: where are the elephants found? This is necessary to target focused studies as well as identify areas for interventions. The Asian elephant lives in a wide variety of habitats, including grasslands, shrub savanna and forests, and can travel up to 188 km² in search of food and water. As they forage, they spend up to 19 hours a day feeding and produce about 220 pounds of dung per day, aiding seed dispersal. These ‘gardeners of the forest’ thus play a crucial role in the ecology of forests, shaping the environment through their foraging habits.

To effectively conserve this flagship species, it is essential to have a clear understanding of their habitat preferences and the threats they face, and accordingly implement targeted management strategies. Earlier survey methods used to estimate the number and distribution of Asian elephants did not properly account for detection bias (not all elephants present are detected during the survey), leading to inaccurate population estimates.

CWS scientists proposed a new, simpler approach known as occupancy modelling to accurately estimate the proportion of available habitat occupied by elephants, using signs such as dung and tracks. These signs are easier to find, even in dense forests or areas with low-density elephant populations. During the dry season between 2005 and 2007, CWS scientists employed this method to study the distribution of this species in the Western Ghats in Karnataka, which harbours one of the largest wild populations of Asian elephants. The survey teams walked the forests, tree plantations, and grasslands in the 38,000-km2 Malenad landscape searching for and counting encounters with fresh elephant dung, tracks, and elephants themselves.

The study (Jathanna et al., 2015) led by Dr. Devcharan Jathanna revealed that Asian elephants had a strong presence in this region, inhabiting 13,483 km2 or 64% of the total suitable habitat in Malenad. Unsurprisingly, their presence was far more strongly influenced by activities such as agriculture, human settlements, and disturbances, rather than just natural features of the habitat. These findings emphasised the critical need to regulate human activities in and around elephant habitats. This study also established a benchmark for rigorously tracking the future distributions of elephants.

Estimating Elephant Abundance Using Individual Recognition and Capture–Recapture Sampling

The photographic capture-recapture method identifies individual elephants based on their unique characteristics. This includes features such as tusk length and shape, ear notch patterns, tail morphology, and other natural markings from their photographs. While camera traps can be used, other forms of manual photography or videography often work more efficiently. Repeated photographic captures coupled with capture-recapture statistical models give an estimate of elephant numbers, as has been demonstrated for tigers and leopards by Dr. K. Ullas Karanth for the first time in 1995.

As elephants are primarily poached for tusks, their vulnerability makes it critical to monitor their populations. Photographic capture-recapture surveys conducted annually over long periods can provide valuable data on changes in population size, survival, and mortality rates among male elephants.

CWS scientists employed this method to identify and monitor individual male elephants in both Nagarahole and Bandipur National Parks in 2006. The study led by Dr. Varun Goswami (Goswami et al., 2007) estimated the population size, survival, and recruitment rates of male elephants (number of new male elephants added to the group). The population of male elephants was estimated to be about 134 in the 176-km2 region, with a recruitment rate suggesting that approximately 12 new males join the population annually. In addition to the 134 males, the study found 571 adult females, 40 male subadults and 102 female subadults, and 145 young, totalling to 991 elephants in the region during 2006. Dr. K. Ullas Karanth said, “The Western Ghats of India harbour the largest population of Asian elephants, a species in retreat all over its range. To guide substantial conservation actions aimed at effectively recovering wild elephant populations, CWS tries to gain reliable knowledge of their distributions and abundances using cutting-edge wildlife science.”

Deepa Padmanaban is a freelance journalist and author. Her stories have been published in The Guardian, Harvard Public Health Magazine, Discover magazine, Scientific American, National Geographic, Mongabay, Frontline magazine and others. She is the author of Rewilding India -The CWS Story and Invisible Housemates ( releasing on August 22nd).

Dr. Krithi K. Karanth is the Chief Executive Officer of the Centre for Wildlife Studies and a globally renowned conservation scientist with over 27 years of work across Asia. Dr. Karanth has received more than 50 awards and recognitions, including the Rolex Award for Enterprise, McNulty Prize, recognition as National Geographic’s 10,000th grantee and Emerging Explorer.