The adage, our roots run deep, is an ancient shared philosophy of existence, not merely in a place at a time but deep in a place and deep in time. As a city-born naturalist eager to explore ‘wilderness’ as some faraway place removed from the schemes of humans, the saying held an immense personal quest: how does it feel to grow roots in a place? Enthusiastic, I wished to bury my roots in the ground when I found myself working in the heart of the country – the Highlands of Central India, as was introduced to the world by one colonial officer a century-and-a-half ago.

As an early-career ecologist, I found myself in the mud in a forest, trying to frame the romanticised picture painted by my city-born imagination – ‘untamed’, ‘untouched’, ‘virgin’, adjectives I grew up with as I looked upon wilderness. Many years before I sat down to write an account of what it really means to grow roots in a place, I was set on a journey through the hills and valleys of central India, only to discover that to go deep, one needs to be tangled with nature. As I busied myself to study this nature, I came to work with the Baiga community, recognised as the first peoples of Central India.

That the tribal communities have been living as one with nature for eons, was a whisper of a thought yet to take hold in my mind. Whatever existed was from the books from faraway lands – a gorilla narrating the reality of human history, as told by Daniel Quinn; the long history narrated by Jared Diamond; the economics of civilisations by Robert Wright. With books of the 19th-century American naturalists and realists, Thoreau, Leopold, and Emerson in hand, I tried to picture nature. I failed.

My first memory of Central India is of an effervescent girl gently smacking a cow about to chomp on someone’s backyard vegetables. Dressed in an old school uniform, the barefooted girl led a line of cattle into the forest. She compelled me to look at myself (shoed, full-sleeved, afraid of ants and mosquitoes), insecure and closed to the world – her world. From my cocoon, I romanticised the forest village life to my infant eyes, and I imprinted on her, and followed like cattle in a line.

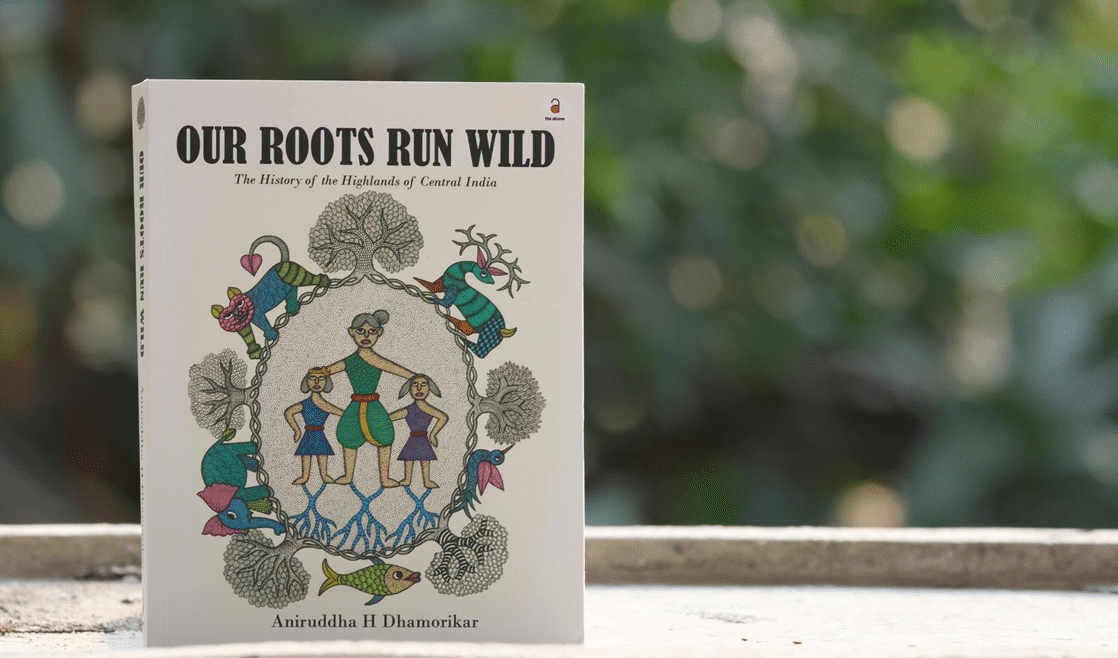

I followed through a tangle of the deep and dark, glorious and haunting, beautiful and depressing, history of the place, eventually becoming a scribe – not a scholar – with a pen in hand, but a learner, a student of history taking notes from the people I met on my travels through Central India. The crux of this book are the tribal communities: it dives into the deep history of the rock paintings, the movement of people and trees, the story of shifting cultivation to sedentary lifestyle, the conversion of a hunter to a poacher, the lessons for human-wildlife interactions – the story of a people and their bond with nature, through the ages of empires, colonial rulers, and the bureaucracy, before delving into the uncertain future in view of climate change.

This is a journey through the past and present of many shared experiences, even as I, the first-person narrator, learns what it takes to grow roots deep and wild. Central India’s literature has focused on its grandeur – its forests, quaint villages, royal lineages, and shikar stories. Many books romanticise the region’s natural heritage without its social context. Forsyth is perhaps the most celebrated because he introduced this piece of land to the world, but in doing so, he, among many others, showed the stereotypical racist and prejudiced outlook the British held for the indigenous peoples. That Central India is a romantic destination, but not without its deep history of blood, sweat, and tears of its tribal and other forest-dwelling folks, is the reason this book exists, even as it seeks to romance the natural heritage of this peoples’ land.

As a scribe, the main challenge was to weave many contemporary narratives together, the past and the present, as well as many investigative cases and theoretical concepts, in view of the future. In doing so, I introduced a part of me as much as of those who wrote before me, with the intent to make the reader feel emotions the way I did, but more aptly, in integrating myself into the book, I wanted to give the reader a chance to realise whether our views match or differ. It was also about mapping my unlearning as a city-born, urban-educated youth – to show what it takes to grow roots in this land.

This is not a book about remoteness – what is considered remote is the soul of India, yet it is a story of remoteness in the view of rights and justice the peoples of Central India have been bereft of. It is also a celebration of the free life, of being barefoot in the wilderness, as much as it is about walking through ancient paths before they turned to highways and ancient forests now turned into rubble for mines. It is a story of the heart of India that continues to beat to the rhythm of the mandar – the ancient drum that still beats in the hills.

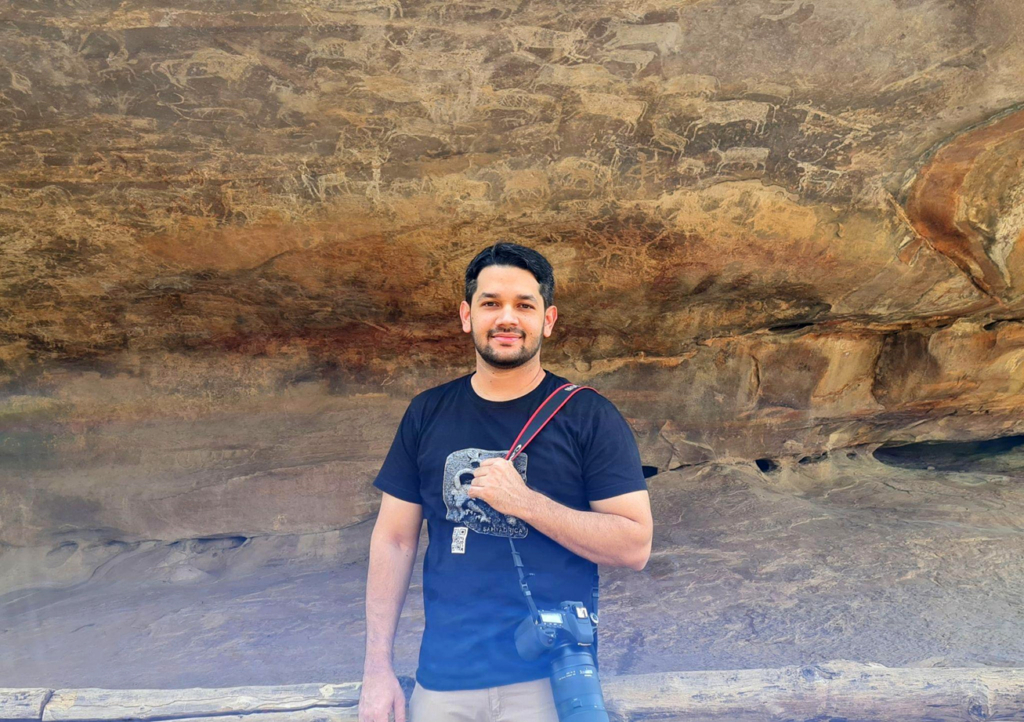

Aniruddha Dhamorikar is an ecologist who has worked in central India for a decade. He has a keen interest in understanding human-nature interactions, which span cultural, spiritual, economic, and material relationships, whether sympathetic or antagonistic. He writes on a range of subjects related to nature, and maintains a blog called Sahyadrica.