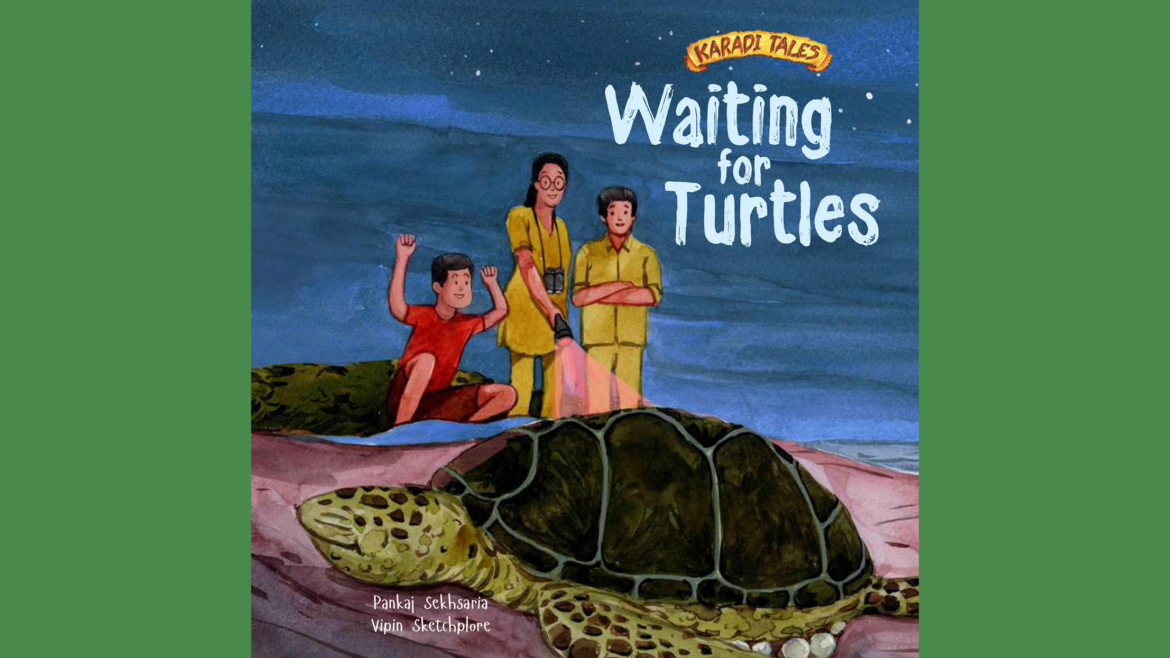

Pankaj Sekhsaria wears many hats. A faculty member at IIT-Bombay, he is also a long time environmental researcher with the environmental group Kalpavriksh and a prolific writer. Well-known for his research and writing on the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, his latest book Waiting for Turtles has just been published by Karadi Tales in English and Hindi. In an email interview with Meghaa Gupta, he discusses his work and life.

How did you get interested in environmentalism and turn your gaze to the Andaman and Nicobar Islands?

Where interest in wildlife and the environment is concerned, the earliest and perhaps the most important influences go back to the time when I was in high school. My younger brother Peeyush was always interested in nature and birds. We used to live in the suburbs of Pune and one of our neighbours had a relative who was a student at IIT-Bombay, a keen wild-lifer and also secretary of the nature club in IIT. He introduced both of us to birding and slowly to the larger world of wildlife, nature and the environment.

The other simultaneous influence was the Cub Magazine and then Sanctuary Magazine, with Bittu Sahgal as their amazing editor. We were keen readers of these magazines that opened up entirely new worlds to us.

There were two other very important influences during junior college. One was my participation in the Western Ghats march, a yatra by a big group of researchers, activists, ecologists, anthropologists and journalists along the mighty Western Ghats to understand the social and ecological challenges. I joined the march for about 10 days from the famous hill station of Mahabaleshwar to Patan in Satara district.

The other was joining the Narmada Bachao Andolan support group in Pune. We would do small events and join meetings that were happening in the city. This made me realise the importance of the questions and issues the andolan was raising – the central one being whose development at whose cost.

These two experiences broadened my interest from just wildlife to the larger canvas of the environment and to the intimately linked issues of equity of human rights and the rights of nature.

My work on the Andaman and Nicobar (A&N) Islands has been serendipitous. I first visited the islands in the late ‘90s and was quite smitten by the place. I wanted to go back and spend time there and also perhaps work there. That worked out first through a project executed through Kalpavriksh that was funded by the BNHS. And then, one thing led to another. I’ve been involved in the place in multiple roles – as a photographer, researcher and chronicler of the islands, in advocacy, as an activist and more recently as a storyteller of tales of and from the islands.

You’ve written fiction and non-fiction on the islands for an adult audience and your latest book is a children’s book. What has been the writing experience between all these different kinds of books, especially writing for children after writing for adults?

Each kind of writing has its own challenges and opportunities. Each has its own identity, purpose and readership. The biggest challenge in shifting from one to the other is to keep this in mind. This is partly limiting, because you might end up circumscribing your story, story-telling and use of language. At the same time, there is the possibility to creatively use the lessons from one kind of writing in the other. For example, academic writing demands a certain kind of rigour and attention to detail, and this can and does bring a similar rigour when one is writing fiction. One has to push boundaries, but also needs to strike a balance. The proof of the pudding is finally in the eating. I might say I’ve written this or that, but it is finally for the reader to tell.

Writing specifically for children was never on my agenda, but neither was it to become an author. However, friends had been telling me for a while to try writing for children. I guess it’s also helped that over the last decade or so I’ve been growing up with my son who is 11 now. And one learns to see the world of the child and the many worlds that a child creates through his imagination. Working with the publishers Karadi has been great too.

In a children’s illustrated book like Waiting for Turtles, while the story and the writing are important, the visualisation and the illustrating are absolutely critical. What Vipin Sketchplore has done for this book is incredible. He’s actually made the book what it is.

Could you tell us a bit more about ‘Waiting for Turtles’?

Waiting for Turtles is the story of a 10-year-old boy, Samrat, who lives in the Andaman Islands with his mother, Seema, a scientist studying marine turtles. These turtles spend their entire lives in the ocean, but the females come to the beaches once a year or once in two years to lay their eggs. It all happens on remote and secluded beaches in the pitch dark of the night, and is one of nature’s most amazing and enduring happenings. Seema’s work involves visiting these beaches and studying these nesting turtles. This book speaks of Samrat’s first field visit with his mother to the beautiful island of Tarmugli in the hope that he will see his first marine turtle.

For most people, the islands are unknown geography. Is there something we should all know about them, especially in light of the recent government decision to develop them?

There are many things about these islands that we don’t know and even a lifetime is not enough. They are beautiful and fragile and unique in innumerable ways. They have to be treated with care when we think of development and that, I think, is not happening at the moment. Mega projects have been proposed here that are insensitive to the geological, ecological and socio-cultural reality of the place and I think, it will be a monumental folly to let them happen.

Other works by Pankaj Sekhsaria

- The Last Wave: An Island Novel

- Islands in Flux: The Andaman and Nicobar Story

- Instrumental Lives: An intimate biography of an Indian Laboratory

- The State of Wildlife and Protected Areas in Maharashtra

- The State of Wildlife in North-East India

- Nanoscale: Society’s deep impact on science, technology and innovation in India