Apart from its on-the-ground conservation projects, the Pune-based Environmental Action Group Kalpavriksh has been publishing thought-provoking environmental literature since the 1980s, including what may well be India’s first graphic novel that came about following a 50-day trek along the river Narmada in 1983. They also have a vibrant and award-winning catalogue of children’s literature on the environment. In an email interview with Meghaa Gupta, Ashish Kothari and Sujatha Padmanabhan from the organisation share their thoughts on the role of environmental literature in shaping society.

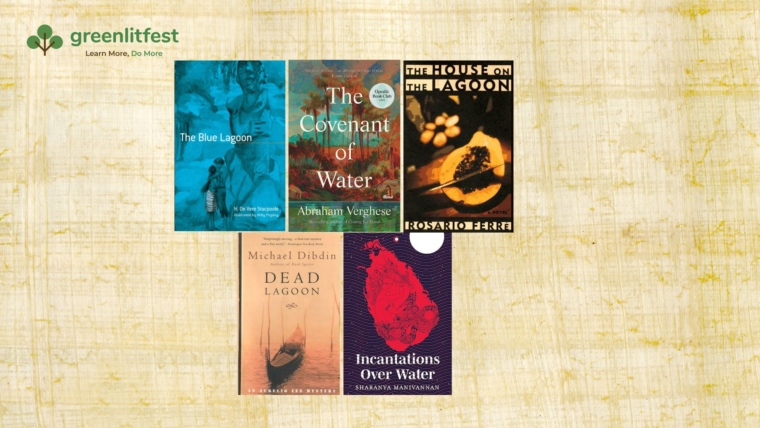

Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring has often been called an important landmark in the environmental movement. Can you think of other books that have shaped the green discourse?

This is a difficult question to answer in brief – in different parts of the world, different books would have been influential. Secondly, we have to remember that in the Global South, oral traditions have been as or if not more important than the written word; stories of historical movements and individuals have inspired people to take up environmental action. Also, it may not be directly environmental literature or work that has shaped the environmental discourse. For instance, the work of Marx and Gandhi, very little of which was explicitly environmental, has nevertheless been of great significance to the environmental movement.

In India, books have often spurred passion and inflamed sentiments. However, these are usually books on popular culture and politics. What do you think is needed for environmental writing to spur a mainstream discourse instead of remaining limited to niches?

Environmental writing has been too cerebral, and mostly restricted to prose. We need much more material that appeals to the heart: poetry and poetic prose, stories of grassroots transformation and collective or individual struggles, material oriented to youth and children, writing that simplifies but does not dumb down the subject, and of course all of this in multiple languages.

A combination of oral and written messaging has been crucial to spreading environmental and social justice awareness, and generating participation in such movements. The songs of Garhwali folk singer Ghanshyam Sailani, which became part of the popular culture of the Uttarakhand hills and were also published and distributed widely, were important in the success of the Chipko Movement. In the movement against the Narmada dams in central India, simply written material and a variety of slogans, songs, and audio-visual messages were vital in generating mass support. Such cultural and literary processes and products are common to most popular movements, not only to create and sustain widespread support, but also to keep up the morale of the movement’s members, especially in the face of state or corporate backlash. These are, undoubtedly, more effective than academic books, though of course those also have their role in spreading the message and generating support amongst urban audiences including students.

Kalpavriksh was founded in 1979. When did you launch your publication wing and what was the thought behind it?

In 1983, Kalpavriksh undertook a 50-day trek along the Narmada river, to understand the valley’s natural and cultural milieu, and assess possible impacts of the proposed large dams. This launched our publications work, as the trek was followed by the publication of three booklets on the Narmada (Narmada Project: A Critique; Muddy Waters; and Environmental Aspects of SSP), as well as a graphic novel a few years later (River of Stories). Interestingly, River of Stories by Orijit Sen was probably also India’s first graphic novel!

Over the past decades, we have consistently viewed publications as one of the important aspects of our work that involves raising awareness, research, advocacy and networking for our thematic focus areas – the interface between conservation and livelihoods, impacts of large dams and other environment and development issues, locale specific environmental education and urban green spaces. We felt it important to share our work through our publications and use them as a vehicle for information dissemination, training and advocacy. All our publications have a copyleft or a creative commons license, which has also helped to disseminate our material more widely.

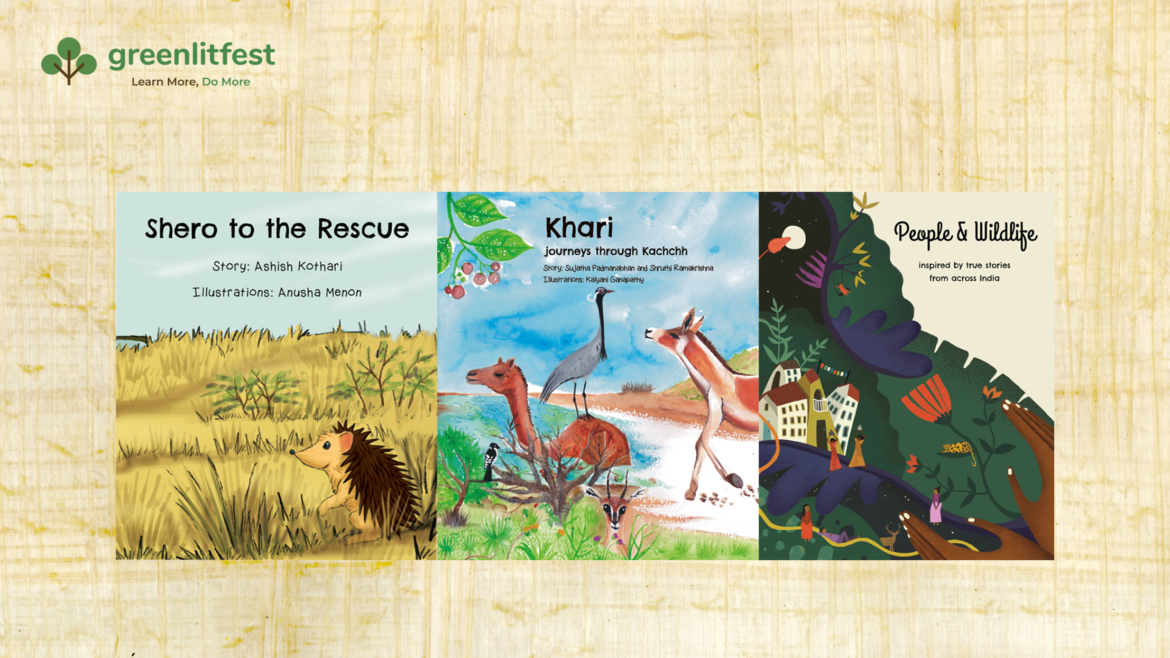

Over the years, you have published some spectacular books on nature and wildlife for the children. Could you shed some light on the state of environmental literature for children in India – the kind of books being published, the achievements as well as gap areas?

In the last few years there has been a sea change in children’s literature in India – not just in books on the environment, but children’s books in general. We see some excellent writing for children, with writers and publishers offering a diversity of books, including those on issues that were never written about like death, disability, caste, other genders etc. And where environmental literature is concerned, there is far greater choice on offer today than say two decades ago, with fiction and non-fiction on wildlife, habitats and ecosystems as well as a range of environmental issues like waste and climate change. We also have books that highlight issues on the ground, like the impact of mining on local communities, community conservation, and human-wildlife conflict.

The wonderful change that we are seeing today is that the stories are not moralistic or prescriptive. Most of them beautifully weave in information about the issue, or habitat and species. Some books also have an element of fun, and will evoke a smile or giggle. Some even tell their stories or share information through verse. And one can’t go without mentioning the work of illustrators who bring these writings to life in a most vivid and brilliant manner!

Many people working in environmental field as researchers, activists or NGO personnel are penning down stories for children based on their rich and grounded experience, and publishing houses are also reaching out to them. Some environmental groups (like ours) are also getting into children’s publications, realising the need for it.

Children’s literature on the environment is also being recognised in India, given that we have children’s literature festivals that sometimes focus on environmental topics.

Of course there are gaps. For instance, some species are written about more than others. Stories on tigers and elephants outnumber stories on other animals. Plants feature less when compared with creatures of the animal kingdom. Similarly, stories situated within some ecosystems such as forests outnumber those set in others like grasslands or wetlands. For older children, the challenge would be to try to see if the stories could deepen the child’s understanding of complex environmental issues as they play out on the ground.

India was among the first countries in the world to implement Environment Education in schools. Yet, the role of suitable environmental literature within the formal education system remains muted. What is the reason behind this and how can one address this situation?

Environment Education (EE) became compulsory in India from the academic year 2004-05. The recommendation by the NCERT is that for grades 1 and 2, it is to be taught only through activities; for grades 3 to 5 it is to be a separate subject with a textbook containing information that would bring alive the local context to the child; for grades 6 to 10 it is to be taught through the infusion method. So textbooks, especially the Science and Social Science textbooks, are to be revised so that links with environment are made in the topics covered, and for classes 11 and 12, it is to be done through a project.

If EE had been successfully implemented, we would have had millions of children growing up as environmentally-conscious citizens! Unfortunately, EE has become a huge challenge for many reasons. If it is seen as a subject and taught without passion, the focus is on marks and passing exams. If it remains at the level of information and does not spur children to change, question and act, then the end goal of EE is not achieved.

EE is most successful when guided by educators who truly care for the envionment, where experiential and outdoor learning is possible, and when a mix of tools is available to the learner. Environmental literature surely has a place in this, but we need government officials who have a vision for EE, and who will recognise how a good story could inspire children to action. How many educational departments have environmental literature as part of a recommended reading list? A few private schools have procured some books for their students and made it part of their EE learning package and some educators skillfully include them in their classroom sessions. But these instances are very few, and much more needs to be done on a national scale.

The best way this could be approached is to first focus EE on local situations that children can relate to, and experientially learn from and find appropriate literature on that issue.