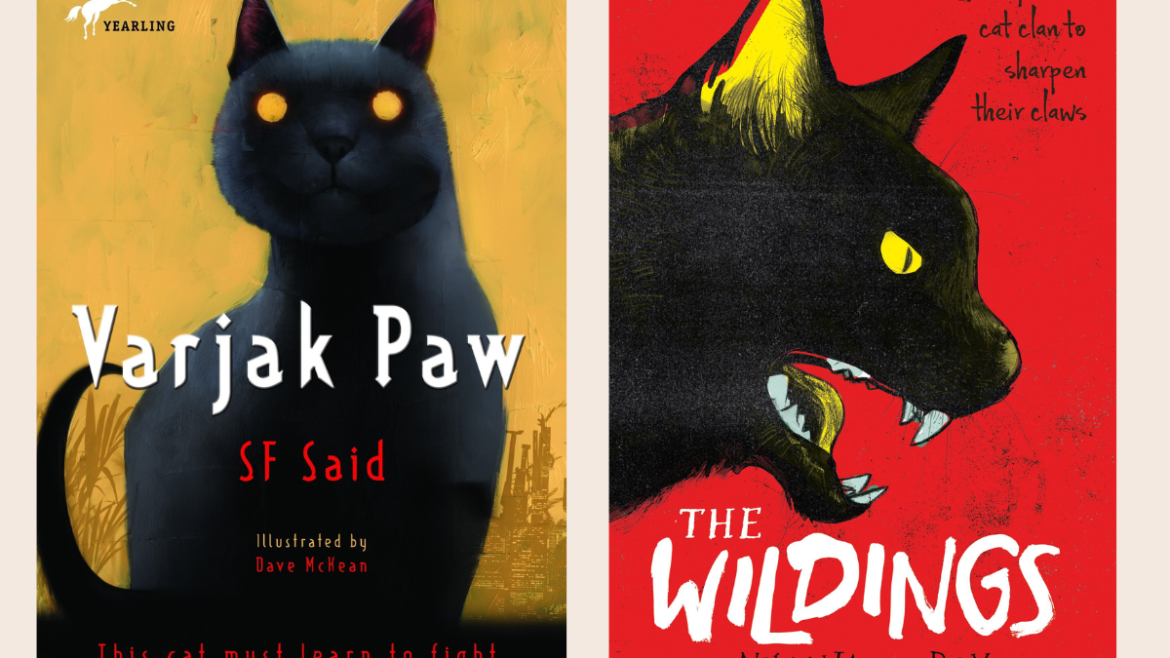

In our third pairing for the literary exchange, we look at feline adventures that explore the ‘wildness’ of domesticated animals.

Varjak Paw is a Mesopotamian Blue kitten, who lives high up in an old house on a hill. He’s never left home, until he receives a mysterious visit from his grandfather who tells him about ‘The Way’ – a secret martial art for cats. Now Varjak must use the Way to survive in a city full of dangerous dogs, cat gangs and, strangest of all, the mysterious Vanishings.

Prowling, hunting and fighting amidst the crumbling ruins of one of Delhi’s oldest neighbourhoods, are the proud Wildings. These feral cats fear no one, go where they want and do as they please. Battle-scarred tomcats, fierce warrior queens, the Wildings have ruled over Nizamuddin for centuries. Now there is a new addition to the clan – a pampered housecat with strange powers that could turn their world on its head.

Meet the Students

This month we have Dharani Dhavamani and Farishta Anjirbag from Ashoka University and Charlotte Taylor and Lexi Dyer from Bath Spa University speak about our book pairing for the month: Nilanjana Roy’s The Wildings and SF Said’s Varjak Paw.

Dharani Dhavamani is a Young India Fellow at Ashoka University. Her research areas include environmental humanities, Indian literature and post-colonialism. She is fond of unearthing South Indian ecological narratives/practices and hopes to work in environmental education and conservation.

Farishta Anjirbag is doing her Master’s in English at Ashoka University. She is a writer and illustrator,

with a great enthusiasm for comics, picture books, and literature about animals – especially cats.

Charlotte Taylor is pursuing the MA in Writing for Young People at Bath Spa and comes to the programme having taught English Literature and Language for more than 25 years. She has a passion for reading, loves writing and is in the process of developing a teen ghost story.

Lexi Dyer lives in Dorset with her family and two very mischievous dogs. She loves all things fantasy and supernatural and writing about found families.

The Discussion

Dharani and Farishta from Ashoka University and Charlotte and Lexi from Bath Spa University speak about Nilanjana Roy’s The Wildings and SF Said’s Varjak Paw and explore the adventures that unfold at the intersection of ‘domestic’ and ‘wild’ worlds, in a conversation with the Greenlitfest’s Meghaa Gupta.

Q. Was this the first time you were looking at writing for young people by an author from India/UK, and what were your first thoughts about the reading experience?

Dharani: Enid Blyton’s books were something that we grew up reading, be it in terms of the detective stories or the school stories like Malory Towers. That was a very strong part of, at least, my childhood and very enjoyable.

Those stories were very human centric and very space centric in terms of the culture, the ways in which human beings interact and how they talk to each other, but in Varjak Paw the central characters are cats. You don’t really have that much of a tethering in terms of the space. So someone like me can easily connect with it, as compared to how much I was able to connect with Enid Blyton’s characters then, because I didn’t know what a scone was, at that point!

Lexi: I hadn’t read anything by an author from India before, but I had read authors who have an Indian background but had grown up in the UK. I’ve read stories that have been set in India and have Indian influences on them. I have read Jasbinder Bilan. She had done the same course that we’re doing. So she was one of our recommended texts and that was how I got introduced to her stories and have read quite a few of them. I have also read a couple of stories by Jess Butterworth. Her grandmother either lived in India or was from India, I’m not sure, but she’s written a couple of stories set there as well. So that was a dipping-your-toe-in kind of experience, as opposed to jumping in fully like this book was.

I found it almost magical seeing this different culture, this different country, through the eyes of cats and it was so different than it would be seeing it through the eyes of a human character, like I’d seen before.

Farishta: As Dharani mentioned, the books we were most exposed to, as children, were by Enid Blyton, Roald Dahl and a bunch of other English authors. There was really no dearth of that in our childhood. This book was lovely. I was really excited to get my hands on it because it was also illustrated and I love picture books. It reminded me of a lot of stuff I used to read and watch as a child. It’s so cinematic, so dramatic. It’s funny. It really holds you even though it’s meant for people who are much younger than we are.

Charlotte: Many, many years ago I read a fantastic book called A Fine Balance by Rohinton Mistry and I think the thing, I’d say, that was kind of common with The Wildings was just the sheer complexity and multi layered-ness of it.

The Wildings reminded me of Watership Down by Richard Adams that was published in the 1970s, where you’ve got these anthropomorphized rabbits, but there’s nothing cute about it. It’s really, really believable.

I started reading it and then I also put it on Audible and if you get a chance, do listen to the Audible version. It’s absolutely brilliant because it sort of brings the novel to life even more with the different voices and sounds.

Meghaa: I’m very glad to hear that because Nilanjana Roy is one of my favourite Indian authors. What’s interesting about this book is that even though in the UK it’s been slotted as juvenile literature, in India it’s very much an adult novel. I wonder what you think. Would you think of this as juvenile literature, probably YA?

Charlotte: I think that it could definitely sit on any adult bookshelf. There’s always this dialogue about whether children’s literature is meant to be inferior to literature for adults. I don’t think that’s the case at all. I think it’s just about the audience. The Wildings is definitely for, I would say, upper upper middle grade, YA. I think you would have to be quite a confident reader.

Lexi: Absolutely. I think a mature upper middle grade audience could handle it. It doesn’t hold back. It’s not necessarily brutal, but some of the fights and injuries, that are described, could be a little bit upsetting for a younger audience. I would have devoured this as a teenager, and a lot of my friends would have. My niece is coming up to 10. I wouldn’t give it to her because I think she’d find some of the hunting and fight parts a little bit too upsetting at the moment. I might give it to her in a couple of years, when she’s a little bit older.

Meghaa: Both the books talk of very domestic cats exploring their ‘wildness’. Are any of you ‘cat people’? Did the books make you view domesticated animals like cats in a new way and ponder the ties that bind the human and non-human world?

Farishta: I wish I was a cat person because I love to look at them, but I can’t bring myself to actually go up to them and befriend them, yet. I think they’re so compelling. You look at them, you want to draw them, you want to write about them, you want to invent little mysteries about them. I think there’s already a lot in our imagination about cats. We’ve seen so much media, so much literature on cats. So Varjak Paw didn’t give me anything particularly new to think about cats, but it really fed into my imagination about them. A new story to look forward to, when it comes to cats.

It was doing a lot of really interesting stuff with the human and the non-human worlds. Both the books [in this dialogue] are set in cities and speak of animals inhabiting spaces that are supposedly human-made. The interaction of those elements was really interesting, because when you think about the natural world you don’t necessarily think about cities. You think about forests, hills and places like that and animals inhabiting those places. And even in these human-made settings, the humans actually take a major back seat. The actual appearance of humans in Varjak Paw is relegated to maybe two or three scenes and there are only two humans we ever hear about in the novel. So we are actually alienated from the human perspective and are made to relate more to the cats. In that sense, the novel gave me a lot to think about, with respect to animal lives and cities.

Lexi: I agree. So I’m a dog person. I’ve had to keep my dogs away so they don’t get too jealous listening to me talk about cats for about an hour or so. I do love cats, I must admit. I would happily have a cat. What I loved about The Wildings, and I think you touched on it a little bit Farishta, is the fact that it’s a very human world that these cats are inhabiting and yet it felt like the world belonged to the cats. I felt like I was almost an intruder in the cat’s world. It was interesting to see what we normally perceive as a domestic animal being very wild and reclaiming this human setting.

I liked how in The Wildings all the cats are wild except for the ones in the Shuttered House who end up being the antagonists and there’s only one good indoor cat. It was really interesting seeing how the wildness was the thing that was being celebrated about these very domestic creatures. The books I’ve read from an animal protagonist’s viewpoint in the past have always been about wild animals. The only exception was The Call of the Wild by Jack London, which is about a domestic dog who then becomes wild.

Dharani: Whatever Lexi said about animals in the house versus the animals outside is very much applicable to Varjak Paw. That’s how the story flows. In terms of the bonds between humans and non-humans, we see the world and explore it through these cats. They are foregrounded. The plot explores themes like intergenerational heritage, things that are being passed down from one generation to the other – ideas about what is sacred, what is celebrated, what is good, what is bad, what is to be retained and what is not. It also shows how things keep changing and sometimes it’s the youngest member of the family who ends up respecting ancestral knowledge as opposed to the older ones who forget about it. This was something that really struck a chord.

Also, as Farishta mentioned, we see cats in cityscapes. That’s how the animals have evolved along with humans, from the forest to the cities. How we have changed, they have changed and we’ve changed together.

Charlotte: I am a cat person. I really like dogs as well, but we’ve had cats in the last few years and it was really interesting reading The Wildings. I read Varjak Paw as well, just to see a different perspective. There’s this thing I’ve seen on TV in the UK where they put a camera on a cat and then they send it out, and people who think that their cat never goes further than the end of the road discover that their cat is actually miles away, totally doing its own thing.

Everyone has spoken about how the humans are relegated to the background. In The Wildings there’s this whole bit where Mara loves the idea of the outside, but then she really likes it when her humans give her a little toy mouse and put her food down in a pretty bowl, and you suddenly see your own role as a human completely flipped. You suddenly realise that these creatures have got like a whole world and we’re just kind of lucky to be involved in it, if at all, and that whole business about the Shuttered House makes you realise that the cats that are kept are at a disadvantage, whereas the cats who are wild hold the key to the city.

Meghaa: What was interesting to me was this whole idea of inside and outside – the inner world, the outer world and exploring boundaries – which is a very human invention. When I finished reading both the novels I felt that even if you had a human character in the place of the cats, the premise would still hold in some ways. I was wondering if anybody had any thoughts on how the novels explore very human concepts through cat protagonists.

Farishta: I’m glad you brought this up because I thought that Varjak Paw does do really interesting stuff with the idea of boundaries. ‘Outside’ is a place of its own for Varjak, who has been raised inside. The ‘O’ is capitalized constantly. It is so much freer, so much more natural. But once he ventures outside, the boundaries begin to get blurred. There is a part where he says the gentleman doesn’t matter in the outside world, but eventually you come to find out that it is the gentleman who has been playing both the inside and outside worlds in the novel. There are his dreams, which bleed into reality. There is this boundary between natural and artificial that’s constantly being confused because Varjak thinks that cars are dogs, and the black cats which look like cats are actually machines.

There is a point in the book where Varjak talks about being free from human dependence and says that he had learned how to survive by himself, but I thought that was the only boundary that actually held up in the book, and I don’t really know how to feel about that because what happens to interdependence between humans and non-humans in a cityscape if you abandon the thought of humans altogether.

Charlotte: I noticed quite a lot of boundaries in The Wildings. The Shuttered House really caught my imagination because there is that sense of the ferals inside, who think that they are at an advantage and we realise that they’re actually at a disadvantage and would have been different if they had been out in the wild with the wildings. I was also thinking about the zoo, the tiger Ozzy and his cub Rudra.

There’s a lot to be explored here about captivity. The tigers have been placed in the zoo by humans and the ferals are in the Shuttered House because of humans and then there is Mara, who could slip her bounds and head off with the wildings but there are things about the human-created, boundaried spaces that are attractive to her.

Lexi: I think the thing with the Shuttered House and Mara, like Charlotte was saying, is quite interesting. What really struck out for me was the fact that Mara’s door is always open, so she always has the choice to go outside, but it’s her choice that keeps her being an inside cat. She’s not quite ready to take that step into the unknown yet. The Shuttered House cats don’t have the choice to go out because, as the name suggests, it’s all closed in. It’s really interesting seeing the effect this has on the different cats and how the ones closed in by force become at a disadvantage and become the antagonists.

We’ve also got the boundaries in the outside world because all the different groups of cats have their own different areas that they’re allowed in and there’s the shrine where they’re all allowed to meet and no one’s going to get in trouble. It’s interesting seeing that idea of boundaries, not just as the walls of houses or the tiger’s enclosure at the zoo but also in the lives of the wildcats outside.

Dharani: In the beginning of the novel, it’s all black and white. For Varjak, the outside space is very exciting because in his imagination it feels like a place where you can be what you want to be, the place from where his mystical, deified ancestor Jalal comes. But for his parents the narrative is different. For them the outside world was a cruel world that Jalal wanted to escape and he found a safe haven in the house. But all these binaries are continuously challenged when Varjak has to go outside. Sometimes he misses home and wants to go back, but sometimes he likes being outside, and there is a section in the novel where he is feels like he belongs in both the places and is the one connecting them.

You can see the blurring of boundaries in the illustrations too. The city and the house are illustrated in black, but when the novel is talking about Varjak’s dreams, the illustrations are grey and you have a kind of a bridge between the real world and the imaginary space. Another thing which was very human was the way in which the cats inside the house – the pure-bred Mesopotamian cats – view the cats coming from outside. They are not pure-bred, so they have to stay out. That kind of a hierarchy reminded me a lot about our own social hierarchies as human beings.

One of the things I wondered was how this novel would have been if the cats were replaced with humans. I think the reason it has been explored this way is the target audience. When younger kids read it, they can connect with the cats to see if, whatever they are thinking and whatever they are being told is similar to what the cats are going through, and they can form that kind of connection.

Meghaa: Are the novels convincing in their animal voice? Were there any bits that possibly felt like appropriation?

Lexi: In The Wildings I didn’t get pulled out of the cat’s world at any point. All the time, I just felt like I was in the minds of the cats. The only time I got a little bit confused was when the perspective shifted between one paragraph and the next and I forgot which cat I was with. The way Nilanjana has captured the behaviour of the cats is just incredible – really small details of how the cats clean like their paws, getting in between each claw, how their teeth chatter just as they’re about to go hunting. I was watching cats in my head do this as I was reading the book.

Even when she sometimes went to other animals, like the birds, the mongoose and the mouse, I didn’t feel like I had stepped away from that animal world or that animal perspective. It was always there. I felt like I suddenly had four legs instead of two and a lot of extra fur!

Charlotte: I totally agree with Lexi. It was so immersive, and I will again recommend listening to the Audible version because the voices were amplified even more. Mara had this shrill, kittenish, piping little voice and then you had the other cats, like Ratsbane and Aconite who were horrible and you could really hear the intent. I was totally invested all the time.

The mouse, Jethro, was my favourite creature. Little Jethro, nibbling away. I thought he was brilliant, and so brave. I would say if I was going to have reservations about any one character it might be Ozzy, because it’s more of an imaginative leap to believe in the tiger than the cat, but that’s me being a bit of a devil’s advocate.

Dharani: I found myself slipping in and out of cat’s world and the human world because there were a lot of similarities in terms of ways in which the characters speak, what they say, family hierarchy, what happens when Varjak goes outside and looks at the wildcats there, and how they speak and their mannerisms.

I feel it is completely fine to have cats speaking in the voice of humans because you cannot know what a cat is actually thinking, what it’s doing. It’s the connection that matters, especially if it’s a child reading the book, and once you’re older, you can understand it from a different lens and talk about the themes and the plot.

Farishta: I was also thinking about what appropriation means when you talk about the non-human because it’s not like we share a common language or any common words of communication that allow us to know what animals are actually thinking and what their inner worlds are like. So I was relating to the cats as I would relate to human characters.

However, there was one moment I found overly confusing. It was when Varjak gets attacked by a tomcat called Ginger because he is in Ginger’s territory, and he refers to Ginger as ‘it’ instead of ‘he’ or ‘she’ and I wondered why a cat is thinking about another cat as an ‘it’.

Meghaa: Last semester, for my MA, I read this book called The Animals in That Country by

Laura Jean. It’s set in Australia and has won a bunch of awards. The interesting thing in that novel was that the animals speak, and the author has invented this strange, halting, not entirely comprehensible language for them.

Q. Do you think young people in your part of the world would be able to relate to these stories? Would they find anything unusual?

Charlotte: One of the things that I’m learning really fast on this MA is that a lot of success of books is about marketing. I think this book is fantastic, but I just wonder how it might be marketed in the UK because if you go into a bookshop, they have tables of middle grade, chapter books, YA, and while it would sit well on a YA table, it’s very different from a lot of YA stuff that’s out there, which is more concerned with human relationships, romance, that sort of thing. It’s a very intelligent book and young people, very often, are very interested in animals and so I think it’s definitely got a market, but I think it would have to be pitched quite carefully and it would need a careful marketing campaign to really find its audience.

Lexi: Yeah, I can see that it might be difficult to find the right way to market it and get it into people’s hands, but I think, once someone’s got it in their hands and they’ve read it, it’s going to spread through word-of-mouth.

In terms of, is there anything people here in the UK might find difficult to relate to, I think, overall, not really. There might be some names for things that they might not know. I mean like, I knew what a cheel was, in the sense I knew it was a hunting bird, but I didn’t know exactly what it looked like. So just for my imagination purposes, I looked it up. But this didn’t take me out of the book enough. I think there might be a few things like references to particular places or smells, for example, that younger people might not be familiar with, in this part of the world. So if that’s described in the book, it’s not going to do anything to help place them in the setting, but at the same time I don’t think it’s going to take them out of it at all.

Dharani: I think people in India would definitely be able to relate to the story and the characters in Varjak Paw because it is not rooted in terms of place. Areas which are explored inside of the house or in the cityscape are kind of universal. If I have to bring in some form of a distinction, it would not be in terms of countries, but it might be more in terms of people living in cities versus people living in villages. For people living in cities it’s common to see cats roaming around in alleys, cats wearing collars and other sights described in the book.

Farishta: India’s demographic is so diverse, it’s hard to speak on behalf of everybody. But I agree with Dharani that for the most part, since the book isn’t rooted anywhere in particular, it is quite relatable. The thing that did stand out for me was that in some places it was a little dark and I found myself wondering whether this was okay in a children’s book. For example, there’s a point at which Varjak is so down in the dumps that he feels it might be better to die than to continue living, and there’s another point at which a non-living cat comes up to Varjak asks to be killed, and I thought that could be a little spooky for kids.

Meghaa: I think, The Wildings was also published in the UK by Pushkin Press.

Charlotte: Yeah, it’s Pushkin Press. I don’t know a great deal about the publishing industry but I think there was a woman called Sarah Odedina who was working there for a while, who was trying to find all sorts of interesting books.

Q. Do you think the way these novels are being told relates to commonly held notions of environmental literature, and how do you think they contribute to one’s understanding of the Anthropocene?

Dharani: Maybe because I was reading the book from an ecocritical perspective, I could pick out some elements, but I do not know if I would have done the same had I just picked it up as a children’s novel. So that is something that I would like to acknowledge in the beginning.

The narrative speaks of how you can build relationships with spaces, inside the house or outside in cityscapes and naturescapes or in terms of connecting with your roots and ancestors, in terms of knowledge. There are also the sections with the dreams where each dream begins with how the land feels, what the fruits smell like, what the river feels like and the sound in the background. In the final dream, Varjak feels like it’s his land and he belongs there.

In terms of the anthropocene, we have the human characters in the house that the cats live in. You have Contessa, who is very caring. She loves the cats and takes care of them. Just looking at them makes her day better. The cats also love being around her. But then you have the gentleman, a cold-hearted, suited man who entices them with caviar but turns out to be an evil capitalist. What he does shows how capitalism has gone on to take greed as its foremost label and everything is seen only terms of profitability.

Lexi: I think The Wildings possibly has more obvious things to say about how humans impact animals and the wilderness. When Ozzy and Rani are talking in the zoo about life in the wild, it’s because they they’re wild tigers that have come into the zoo, whereas their cub has not really known any place other than the zoo. When Mara talks to these two older tigers, they speak about how their cub Rudra has been taken away, to a different enclosure because he is old enough to breed. Obviously the zoo has a breeding programme trying to get tiger numbers up, which we as humans see as trying to help the tiger population, whereas the tigers are more concerned about the fact that their cub has been taken away and how in the wild he would have been with them for longer. But Rani also points out that in the wild he may not have made it this far and they talk about poachers, and smoke from forest fires created by villagers that chokes cubs. It was interesting seeing how the tigers were talking

about the benefits of being wild and free, but also the benefits of being in the zoo and having that level of safety. It was almost like a slap in the face to see how humans impact wildlife.

Beraal also remembers when she was trapped in a crate and these children tied milk bottles around her tail. She talks about how long it took for her to escape from the crate and then to chew through the cord that was tying the milk bottles to her tail. It reminded me of how cruel we, as humans, can be towards animals either on purpose or accidentally. Even the man who owns the cats in the Shuttered House obviously cares very deeply for them, but his love has not done them any favours. It has almost corrupted and twisted them in a way because he’s kept them so sheltered.

Even though it was a bit of a slap in the face to see the impact that humans have, it never felt like it was being preachy or I was being hit round the face in a way to say ‘you need to do better as a human.’ It opened your eyes to things that you already knew, but you were seeing them from a different perspective.

Meghaa: Do you have an ecocriticism module as part of your MA, Lexi and Charlotte?

Lexi: We don’t. One of the ladies in one of my workshops is writing a book on climate crimes. That’s kind of the closest I’ve gotten to discussing environmental issues in the MA.

Farishta: Picking up from what Dharani was saying earlier, your first guess wouldn’t be to look at this from an ecocritical perspective because it’s not explicitly talking about saving the environment, how the environment is being destroyed, or anything of the sort. But it does deal with the environment in very interesting ways. I think our conversation about the city reflects that, because ecocriticism is also increasingly leaning into urban environments and exploring notions of nature in those spaces.

In Varjak Paw we’re constantly alternating between the very natural space of ancient Mesopotamia and the new urban space of the city that Varjak lives in. Throughout the novel he is coming into his own and living in tandem with both these spaces. So as Dharani said, by the end of the book he belongs to both. He is one with them.

As regards the anthropocene, human appearance is minimal in the book, but human presence is constantly felt because the main threat to their lives is from humans. But the book does not focus on that. It places the animals in an anthropocentric world but shows that the anthropocene belongs as much to the non-humans.

Charlotte: Lexi said a lot of things, which she articulated beautifully. I think The Wildings is a fascinating study of ways in which humans and the animal world interact. It is not about climate change, which is something very current and deservedly so, but it does plunge you into an environment where you think about the setting, the streets, the twigs, the alleyways and the river. You are very much thrown into the natural environment and develop a real respect for it.

In terms of the anthropocene, I feel the reader realises that even though humans may try and impose their will on the natural world, it is much more vigorous and stronger than humans can counter for. It is interesting about the man in the Shuttered House. He really does care for those cats, but actually his contribution is to turn them sour and make them these angry, horrible, feral creatures. Whereas the wildings live within the natural order. Their world is quite cruel sometimes, there’s bloodshed and harsh hierarchy, but it somehow allows the wildings, the cheels, the mice and the mongooses to be themselves and thrive.

Q. Book recommendations from your countries that you think that others in other geographies should know about.

Farishta: I have three books to recommend.

Moonrise from the Green Grass Roof by Vinod Kumar Shukla has been translated from Hindi into English. It’s a great read for children. It’s set in a village and there’s a mountain near the village that has a mysterious hole in it. The book associates this mystery not just with the everyday life of the village but also with the much larger cosmos.

My second recommendation is a collection of ghost stories by Ruskin Bond. These stories are set in the hills of Dehradun and Mussoorie and derive from myths and legends that are set in the natural environment of these places.

My last recommendation is Namita Gokhale’s Things to Leave Behind that plays out the intricate ways in which local people’s lives are tied to the lakes in Nainital.

Lexi: The books I am going to recommend have crept right to the top of my to-be-read pile.

The first one is The Last Bear by Hannah Gold. It’s about the extinction of polar bears on this island and how this girl is trying to bring them back.

The other recommendation is The Last Whale by Chris Vick. I was at the launch event for this book and heard the author talking passionately about what the book was saying about the human impact on the environment and that persuaded me to buy it.

Jess Butterworth has also written a lot of fantastic books on the environment. My favourite is

Running on the Roof of the World.

Charlotte: There is this really beautiful book called The Lost Spells by Robert Macfarlane, who writes a lot for adults. It’s like a book of spells that try and summon nature where there seems to be none. You will find incantations and summoning charms. Spells that protect and spells that protest. Tongue twisters, lullabies and psalms. It’s very much about noticing nature before it’s gone. His other famous book for children is The Lost Words.

I have read The Last Bear and I think it’s a great book for kids.

When I was a teacher, a lot of children were interested in The Last Wild by Piers Torday. It’s about a boy who finds himself on the final frontier, before the Earth perishes.

MG Leonard has this new picture book called The Tale of the Toothbrush about what happens to an indestructible toothbrush.

Dharani: As a child I heard a lot of stories from the Mahabharata and Ramayana epics from my grandparents and versions of those might be a good place to start off.

Malgudi Days by RK Narayan is another recommendation that comes to mind when I think of stories that tie up the daily lives of people in India with the environment.

Janice Pariat’s Boats on Land is a fantastic collection of short stories from north-eastern India.

The Hungry Tide by Amitav Ghosh is, I think, an obvious recommendation. It is set in the Sundarbans and talks about the people living there, the politics of the land and its wildlife.