What does it mean for a literary work to have land as the protagonist? Land and its accompanying tales have contributed to the social, mental and spiritual construction of space. What role did landscapes play in the journey of societies and their understanding? Poet and philologist Kanya explores the enchanting intricacies of land in fiction.

‘So listen as I tell you your journey’s right route

Later, water-giver, you’ll hear

my message with your eager ears

Placing your feet on peaks,

weary, ragged,

You’ll sip some water from streams

and be on your way.’

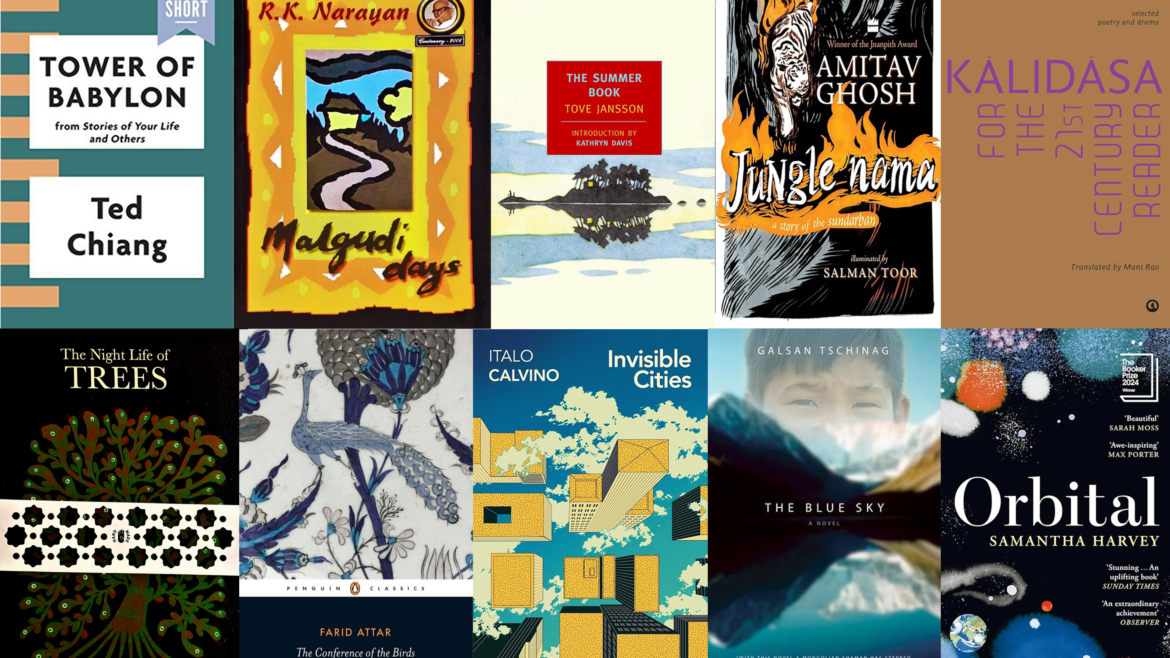

— translated from the Sanskrit by Mani Rao, Kālidāsa for the 21st Century Reader: Selected Poetry and Drama

In Kālidāsa’s Meghadūtam, a cursed yakṣa exiled to the Vindhya mountains of central India is trying to make his case before a passing cloud. His beloved lives in Alakā, in the far reaches of the Himalayas, and he needs the cloud to take her a message. The story setup is also a device for describing the beautiful landscapes along the cloud’s path.

This is a famous example of a Sanskrit sandeśakāvya, message/messenger poem, an old Indian tradition of setting nature descriptions within verse fiction. Uṇṇunīlī Sandeśaṃ in Manipravalam, similar, is one of the oldest texts in the composite language that draws from Sanskrit, Tamil, Malayalam, Telugu, and Kannada. Several other texts, too, follow this pattern.

How could we have helped it then, and, indeed, how can we now? Seventh greatest in landmass and one of the most biodiverse countries on earth—megadiverse, they’re called—India has landscapes that could make story after story and never run dry. Their mindbending multiplicity and sheer range bolster us, prepare us to go farther and deeper. Here are a few beguiling lands from unusual fiction—some set in India; some elsewhere in the world, but kindred in spirit.

Lands of Lore and Legend, Fable and Fantasy

‘You’re going to the tideland where dangers are legion.

In the mangrove forest many strange things happen.

It’s the land of Dokkhin Rai, a hungry shape-shifter;

he hunts humans, in the form of a tiger.’

— Amitav Ghosh, Jungle Nama: A Story of the Sundarban, illuminated by Salman Toor

Something strange is going on in the mangroves of the Sundarbans. Drawing from Bengali epic poems and setting the jungle scene, Ghosh recounts the folk legend of Bon Bibi in verse. In such lands of dreaming and knowing, what is real and what is unreal cannot quite be separated. In Farid ud-Din Attar’s 12th-century Persian epic poem The Conference of the Birds, rendered in illustrated form by Peter Sís, all manner of birds led by a hoopoe fly a perilous path to the mountain of Kaf, where Simorgh, the king of the birds, lives. What happens when they finally meet the king? In RK Narayan’s unforgettable Malgudi Days, the land itself is fictional—the sleepy South Indian town of Malgudi. The town may be tranquil, but the days are full. OV Vijayan, too, builds a fictional land, Khasak, in his Malayalam novel Khasakkinte Itihasam (The Legends of Khasak is a bit different even in his own translation). Before we’d ever heard of magic realism, we had Khasak. And it felt perfectly right.

Lands of Earth, Water, Fire, Air, and Space

‘We walked back home unhurriedly. Grandma pointed to the birds clamoring and romping in the air, and the flowers piercing the ground and rising from the steppe around us in a multitude of colors like glittering splashes that had drizzled down from the sun, the sky, the glaciers, and from mountain ridges that seemed to smoke and blaze with all this light.’

– Galstan Tschinag, The Blue Sky, translated from the German by Katharina Rout

There were times and places where no one needed to be told that they were already part of nature. In The Blue Sky, in the high Altai mountains of northern Mongolia where the old and the new rub up against each other, Dshurukawaa, a Tuvan shepherd boy, learns the ways of life. In The Summer Book by Tove Jansson, translated from the Swedish by Thomas Teal, six-year-old Sophia spends a summer with her ‘very old grandmother’ on a ‘very small island.’ But there is an absence between them, the child’s mother who is dead. Land and life and love. In Samantha Harvey’s Booker-winning Orbital, six astronauts and cosmonauts aboard the International Space Station circle the lone blue planet 16 times a day, feeling its tender, awesome, inevitable pull. In Tara Books’ exquisite The Night Life of Trees, three Gond artists—Bhajju Shyam, Durga Bai, and Ramsingh Urveti—evoke a magical world where trees ‘are busy during the day, giving shade and food to humans and animals. It is only during the night that their real spirit emerges.’

Lands Before, Between, and Beyond

‘There is a sense of emptiness that comes over us at evening, with the odor of the elephants after the rain and the sandalwood ashes growing cold in the braziers, a dizziness that makes rivers and mountains tremble on the fallow curves of the planispheres where they are portrayed, and rolls up, one after the other, the despatches announcing to us the collapse of the last enemy troops, from defeat to defeat, and flakes the wax of the seals of obscure kings who beseech our armies’ protection, offering in exchange annual tributes of precious metals, tanned hides, and tortoise shell.’

– Italo Calvino, Invisible Cities, translated from the Italian by William Weaver

Kublai Khan, the emperor of the Tartars, holds an ongoing conversation with the Venetian traveller Marco Polo, within which cities after cities appear and disappear. In Ted Chiang’s Tower of Babylon, Hillalum and other miners ‘dig through to the vault of heaven.’ But where is heaven and where is earth? In Jeff VanderMeer’s Annihilation, the first of the Southern Reach series, an expedition team—comprising a biologist, an anthropologist, a psychologist, and a surveyor—sets out into Area X. But what exactly is Area X? An expedition of a different kind awaits in Jean “Moebius” Giraud’s graphic novel The World of Edena, a ‘fabulous cosmic drama,’ with Stel and Atan, its ‘two goodhearted protagonists rediscovering humanity’s true state of being.’

Why have we been looking for lands in fiction in the first place? Moebius says at the beginning of the book, ‘… I did not lose everything I had, but I did not find everything that was lost.’ If we flip that around, we might get an idea: We may not find everything we lost, but we will not lose everything we have.

Kanya Kanchana is a poet and philologist. Her work has appeared in POETRY, The Common, Asymptote, Longreads, and elsewhere. (enchantedforest.substack.com)