On an exceptionally bright monsoon morning, I walked into the gates of Upstream Ecology in Ooty, one of its kind nurseries focusing on the regeneration of native species in The Nilgiris Biosphere. The person behind this initiative, Godwin Vasanth Bosco, settles for a conversation after showing me around the well-kept saplings that would soon grace the ancient mountain slopes.

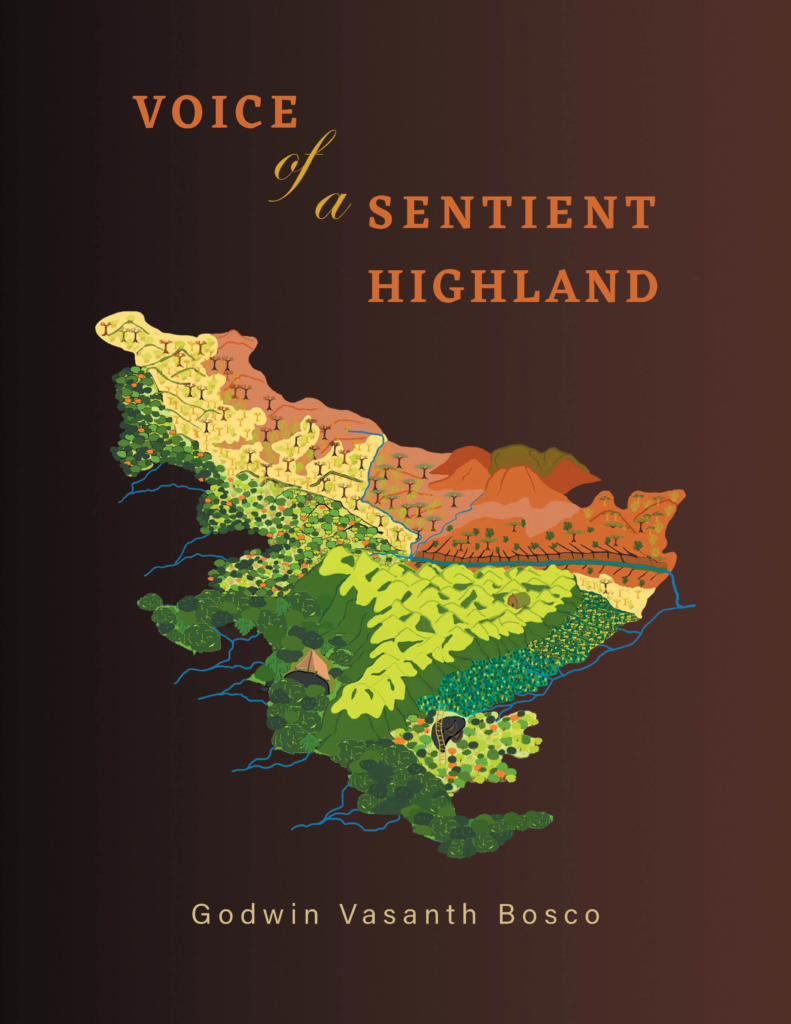

Vasanth Bosco is a restoration ecologist, researcher and author of Voice of a Sentient Highland ((Upstream Ecology Publishing, 2019)). He is also the co-founder of Iyarka, a plant-based products research company. His work has appeared in several publications, including The Hindu.

Vasanth’s book is a vast story of a mountainscape, its glorious history and ecology, highlighting the dynamics of change governing the land and the environmental resistance the future needs. A visually rich narrative with images and illustrations, the book takes a reader through the slopes, valleys, plateaus and peaks of The Nilgiris, spotlighting its pristine habitats, native trees, shrubs and grasses along with the invasive species. Edited excerpts from our conversation:

Your book was the result of nine years of extensive groundwork, research and toil. It drew attention towards a landscape that was otherwise known only for its tourism. How do you look back on that journey?

The time I spent on this book was the best part of my life. Walking and exploring this landscape was a long-time dream. I was born in Ooty and I went to school in Chennai. During my vacations here in Ooty, I had longed to connect with this land deeply and working on this book gave me that opportunity. In the first few years, I journeyed across the terrain and learnt from people who knew this place better. Then, I focused on learning about the species that are a part of this biosphere, and later, ground action and work began.

Your book deeply explores the themes of environmental invasion, exploitation and resistance. Do you think it is too late for resistance, not just in The Nilgiris but in ecologically sensitive regions across the world?

There is a chapter in my book that explores resilience. The term is extensively used in ecology and green discourse, and it gives a sense of hope. However, I think resilience as a concept is misunderstood. Of course, nature is extremely resilient, and once our destructive methods stop, the land will bounce back. However, the magnitude of destruction is far greater than the opportunities for revival that are being given to nature. All over the world, two hundred species are going extinct in a day.

The chapter after in my book is called Beyond Resilience, where I speak about ground action and responsibility. A city dweller experiences climate change in heat waves, cyclones or droughts, but we know the public memory is short. We have to be in touch with landscapes with remnant tracts of nature to know the magnitude of the problem and to understand what can be done. For people in South India, a place like Nilgris gives that window of opportunity.

A Shola Forest is an intricate system. It has been your work environment for more than a decade. Having studied the forest as intimately as you have, how do you connect to the forest?

For me, a Shola is an extremely beautiful, complex, intelligent, and evolved community of plants and trees. Certain conditions set the forest and grassland apart. The light, moisture, and soil vary in both. I see them as a metaphor for balance between two extremes: the dark density of a shola and the complete exposure of the grasslands.

Given the unique biogeographical composition of the plants here, this is where the two extremities meet, and the ecological messages from here are important. This is why I have referred to this place as ‘sentient highlands’, and there are seven messages in the book from this biosphere. From the ground level to the philosophical, it is extremely engaging, and it helps me perceive better.

What challenges did you face in documenting a landscape as complex as the Nilgiri biosphere, or to use your own term, as sentient as this region, and in capturing those intricacies into text?

There were several. Documenting the information clearly was a huge task and I followed a novel method in structuring the narrative. I am more of a visual learner and I haven’t read many books. I could visualise every concept and stack them up in order. This helped me categorise everything I have learned over the nine years. I built a complex image in my head and slowly unravelled from there. I designed the book, its layout and handled the illustrations. Only this aspect of the book took more than a year to complete.

Is there a reason you chose to self-publish your work?

I wanted to have my own design and structure. A reader can find small columns on certain pages with a summary of the contents on the page. For a person not interested in the details, a glimpse through the boxes can give them the necessary information. I wanted to retain this layout to make it easy for the reader.

You have written in-depth about grasslands and even taken on regeneration work through Upstream Ecology. You mention the challenges that cloud regeneration, namely, excess carbon and climate change. How do you work around these challenges on the ground?

The carbon levels in the atmosphere are tricky. The plants that we work with may be affected in the long term, and invasive species also have an advantage. We do our best to give space to native species, the endangered ones and plants that are naturally adapted to climatic changes. In our restoration activities, we also focus on the shrubs. They tend to grow faster and are capable of handling pressure. Overall, grassland and shrublands are considered more reliable carbon sinks since most of the storage happens below ground. We work extensively with them and the resultant carbon sequestration that can happen is a significant benefit.

In some chapters, you refer to indigenous knowledge. What do you think the collective ecological knowledge of the communities in The Nilgiris can offer in the Anthropocene?

I don’t know of any landscape that has supported an array of indigenous communities the way The Nilgiris has. These communities’ knowledge and relationship with the land are complex and deep. There is a huge disconnect between their knowledge and the world’s perception of it. It is not necessary to document and learn everything like a stream of science, but valuing their expertise and grasping their basic sentiments about the resources is essential.

Throughout the book, you have avoided adopting a critical tone on the changes that the land has undergone or land use policies influencing our time, such as the monocultures and plantations in the mountains. You have stated the facts but with limited criticism or pinpointing. Was that intentional?

The book was about documenting and collecting first-hand information, and I wanted to have a tight narration. I did not want to share too many opinions that were not based on facts. However, in the last chapter, I shared my views on how we need to act to save the future, for example, by reducing industrialisation by 60%.

Some of the thinkers who have inspired you.

I deeply admire Derek Jensen. My mentor and teacher, Suprabha Seshan, has written extensively, and every conversation with her is always inspiring.

Do you follow nature writing in India? Are there any peers or contemporaries you admire?

I have to catch up on a lot of reading. I plan to read Marginlands by Arati Kumar-Rao and Yuvan’s Intertidal soon.

What are you currently working on?

I am expanding on this sentient concept of land in a book titled Mountains of Intelligence. I am also working on another book that expands on my alternative economic theory for change and how to approach it.

Finally, a word of advice to nature writing enthusiasts.

Firstly, explore, focus on research, and gather as much information as possible. It takes time to understand the land and make an impact. Nature writing is a journey laden with hurdles. It is easy to lose focus along the way, and self-doubt is inevitable. One needs to have a lot of patience and determination to sail through the blocks. However, you have the biggest source of inspiration and portal of wonder on your side—nature.

Monisha Raman’s essays and short stories have appeared in several Asian and international journals. Her work can be found at https://linktr.ee/Monisharaman.

Vasanth Bosco is an author and restoration ecologist. He is also the co-founder of Iyarka, a plant-based products research company. His work has appeared in several publications including The Hindu.