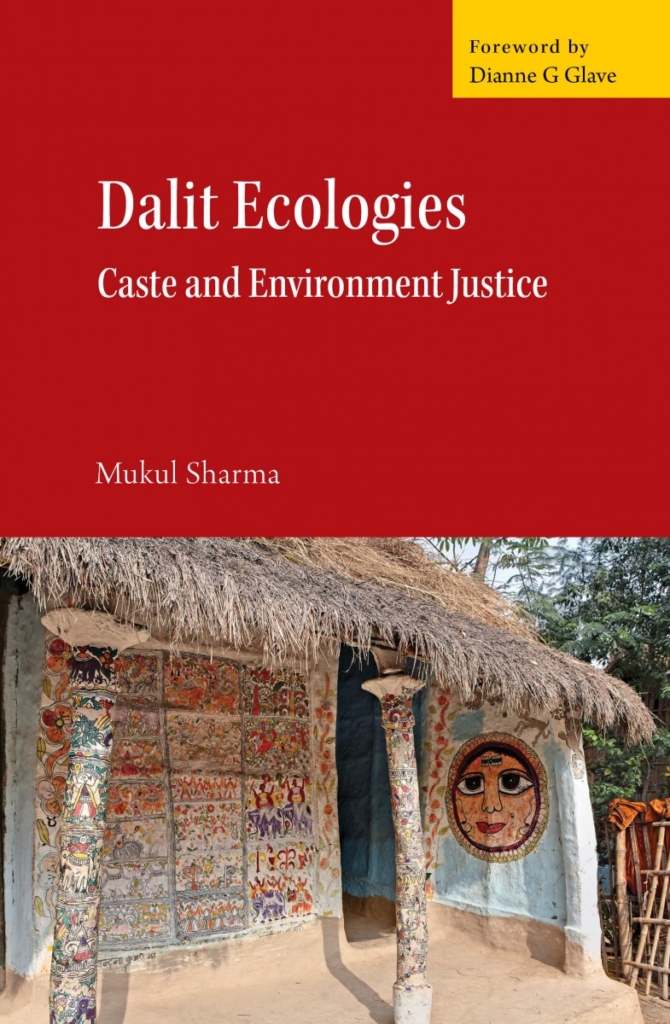

Mukul Sharma is a professor of environmental studies at Ashoka University in Sonepat, Haryana. His book Dalit Ecologies: Caste and Environment Justice (2024), which is a sequel to his work Caste and Nature: Dalits and Indian Environmental Politics (2017), is shortlisted for the Green Honour Book Awards in the Fiction/Non-fiction category. Published by Cambridge University Press, it draws attention to the erasure of caste from the mainstream environmental justice discourse in India and champions Dalit perspectives to challenge “eco-casteism”. In this interview, he discusses his academic research as well as his pedagogic practice in detail.

What led you to think and write about environmental justice from an anti-caste perspective/standpoint?

My intellectual journey began with noticing the silences in Indian environmentalism. Canonical works such as Ramachandra Guha and Madhav Gadgil’s This Fissured Land powerfully traced ecological histories, yet caste barely appeared in their analysis. The environmental struggles of Dalits—whether around land, rivers, sanitation, or industrial labour— remained invisible. Environmental justice discourse has indeed acknowledged plurality, diversity, and locality, but caste and Dalit experiences have not been adequately recognised or integrated. It is within this gap that my anti-caste and Dalit critiques of environmental justice have emerged.

In such contexts, I examine, for instance, how leather work—historically imposed upon Dalits—is simultaneously an ecological practice, and a site of deep humiliation. Autobiographies such as Omprakash Valmiki’s Joothan or Bama’s Karukku vividly narrate environments of exclusion—unclean lanes, polluted neighbourhoods, and segregated wells. These texts demonstrate that caste is not only a social relation but also an environmental one.

Globally, I was influenced by African American scholars such as Robert Bullard and Dianne Glave, who have shown how race shapes access to clean air, water, and land. Their work prompted me to ask: what might it mean to speak of “eco-casteism” in India, where caste, much like race in the United States, structures ecological inequalities?

How would you unpack the term “Dalit ecologies” for readers who are not well-versed with scholarly debates in the field of environmental studies?

Dalit ecologies mean taking seriously the environments that Dalits inhabit, endure, and transform. For instance, I look at the tannery industry in Kanpur, where Dalits and Muslims historically worked. The polluted river and toxic leather work are not just occupational hazards but lived ecologies of caste. Similarly, brick kilns—often staffed by Dalit migrants—reveal how labour, land, and caste intersect in ecological degradation.

Dalit ecologies also include creative responses: folktales of Deena-Bhadri in Bihar and Uttar Pradesh, or the Rock Garden in Chandigarh, which show how waste is remade into culture. These examples remind us that ecology is not pristine nature alone but is shaped by histories of caste oppression, displacement, and resilience.

Dalit ecologies also engage with newer themes of environmentalism, such as industry, technology, climate change, the Anthropocene, big capital, and the market. In these areas, I examine how caste shapes the experiences of Dalits and other marginalised communities, and how they articulate their environmental concerns and struggles across different locations.

In this sense, Dalit ecologies parallel what scholars like Carolyn Finney (author of the book Black Faces, White Spaces) describe for African Americans—how excluded groups imagine and inhabit landscapes differently from dominant narratives.

What do you hope to achieve with this book, in terms of contributions to both scholarship and society?

At one level, I seek to broaden environmental scholarship by emphasising caste as constitutive of ecological injustice. Just as ecofeminism redefined environmentalism by asking “Where are the women?”, I ask, “Where are the Dalits?”. This is a question that reorients the field. I also aim to build an archive of Dalit literature and culture that can serve as a vital resource for understanding the entanglements of caste, Dalit experience, and the environment.

At another level, the book seeks to offer recognition. When Dalit women like Narsamma Masanagari or Manjula Tammali resist exclusion in global climate spaces, or when writers like Bama and Valmiki narrate their ecological experiences, their knowledge must be acknowledged as environmental thought. By centering these voices, I hope the book contributes to a more just ecological discourse—within both universities and environmental movements.

In the introduction, you quote an unnamed activist who said, “Dalits are not afraid of climate change or any other natural disasters because socially and economically, they have been leading a disastrous life forever. For them, disaster caused by upper caste Hindus is the real problem.” To what extent are environmental justice movements in India open to such critiques of how the climate crisis is framed?

The quote cuts through the abstraction of climate discourse. It echoes Omprakash Valmiki’s description of Dalit childhood as a constant exposure to dirt, filth, and humiliation.

Mainstream environmental movements—like Chipko or Narmada Bachao Andolan—made significant interventions but often universalised suffering, sidestepping caste. Even today, much climate advocacy in India speaks the language of emissions, renewable energy, or global justice, but not caste injustice.

There are shifts, however. The National Dalit Watch (set up after the 2004 tsunami) highlighted how disaster relief was caste-biased. Anti-caste organisations have also joined climate forums, pointing to the everyday “disasters” of manual scavenging, displacement, or polluted work. Yet, compared to feminist or Adivasi critiques, caste perspectives remain underacknowledged in mainstream environmentalism.

Your chapter on Nek Chand, the creator of the Rock Garden in Chandigarh, made me think of Lavanya Karthik’s recent biography The Boy Who Built A Secret Garden. While it acknowledges his background as a Partition refugee, it does not engage with the fact that he “belonged to the Mali caste”, as you mention. What made you tell his story using the concept of the “Dalitbahujan Anthropocenes”?

Answer. Nek Chand’s Rock Garden in Chandigarh is often celebrated as outsider art, but rarely through caste. He belonged to the Mali caste, historically associated with gardening. After Partition, as a refugee, he collected urban waste—broken bangles, tiles, ceramics—to build a spectacular ecological art.

By framing this in terms of the Dalitbahujan Anthropocenes, I argue that subaltern lives produce alternative planetary visions. Instead of focusing only on elites’ role in the Anthropocene (fossil capital, overconsumption), we must also attend to how marginalised groups work with waste, fragility, and creativity. Nek Chand’s Rock Garden is not simply aesthetic—it is a testimony to survival, displacement, and ecological re-making at the time of great acceleration in India.

Similar moves are made by scholars like Malini Ranganathan, who highlight subaltern urbanisms. I extend this to argue that Dalitbahujan experiences produce planetary imaginations that unsettle universal Anthropocene narratives.

As a professor of environmental studies at Ashoka University, which is known to cater to the elite, how do students respond to the inclusion of Dalit autobiographies and memoirs in discussions of environmental justice? What kind of pedagogical strategies do you use to help students examine and wrestle with “climate casteism” (an idea you mention) out there in the world but also within themselves?

At Ashoka, many students come from privileged backgrounds. For them, reading Dalit autobiographies alongside environmental texts can be transformative. When they encounter works like Baby Kamble’s The Prisons We Broke or Bama’s Karukku, they are compelled to rethink “environment” not as distant forests or abstract climate concerns, but as caste-segregated villages, polluted neighbourhoods, and stigmatised occupations.

Pedagogically, I encourage reflective journals where students trace their own positionalities. For instance, after engaging with Bezwada Wilson’s writings on manual scavenging, many students are prompted to confront their own caste locations and privileges. Group discussions on what I call “climate casteism”—the caste-differentiated vulnerabilities to climate impacts—help them recognise how privilege shapes not only environmental realities but also their ecological imaginaries. The aim is to move beyond personal sympathy toward a deeper awareness of political and social ecology.

My two courses at the university—Environment and Social Exclusion, and Environmental Justice—both of which foreground caste, Dalits, and ecological issues, have been widely taken by students. Their participation in these classes has been, for me as a teacher and researcher, a genuine eye-opener.

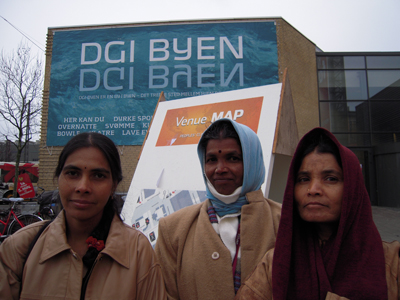

You note that three Dalit women (Narsamma Masanagari, Manjula Tammali and Sammamma Begari) from Andhra Pradesh burnt their accreditation badges at the United Nations Conference on Climate Change at Copenhagen in 2009 to protest “the lack of recognition of caste and Dalits in climate discussions”. What has changed in the decade and half that have passed since that protest?

That protest dramatised the invisibility of caste in global climate debates. Since then, recognition has remained limited. Frameworks like the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) continue to operate with categories such as “developed/developing” or “North/South,” which effectively erase caste as a lived reality.

At the same time, grassroots voices have grown stronger. Organisations like the National Campaign on Dalit Human Rights (NCDHR) and various Dalit women’s groups have become increasingly vocal at climate forums, while social media has amplified Dalit environmental perspectives. A growing number of researchers and academics are also beginning to engage with the intersections of caste and climate injustice.

The difference today lies less in institutional transformation and more in a louder insistence that caste must be recognised as part of climate justice. Yet much remains to be done. Caste is still largely absent from policy documents and international reports on vulnerability.

You refer to the work of Black intellectuals in challenging racism in environmental justice discourse in the United States. What challenges come up while adapting these ideas to the Indian anti-caste context?

Black intellectual traditions—from W.E.B. Du Bois, Robert Bullard to J T Roane—show how racism structures environmental burdens. These insights resonate with Indian realities. Just as African Americans are more exposed to toxic waste, Dalits often live near dumpsites, tanneries, or drains. But there are differences. Race and caste operate through distinct logics. While racial segregation is often spatial and institutional, caste includes ritual notions of purity, hereditary occupations, and religious sanction. This makes “eco-casteism” distinct from “environmental racism.”

The challenge is to draw comparisons without collapsing differences. Works like Suraj Yengde’s Caste Matters and Anupama Rao’s The Caste Question help bridge these contexts. I find inspiration in how Black ecologies (Dianne Glave, Carolyn Finney) reclaim landscapes from exclusion, and I argue that Dalit ecologies do something similar—insisting that polluted drains, waste sites, and degraded lands are also sites of ecological knowledge and justice.

Chintan Girish Modi is a journalist, educator and literary critic. He can be reached @chintanwriting on Instagram and X.