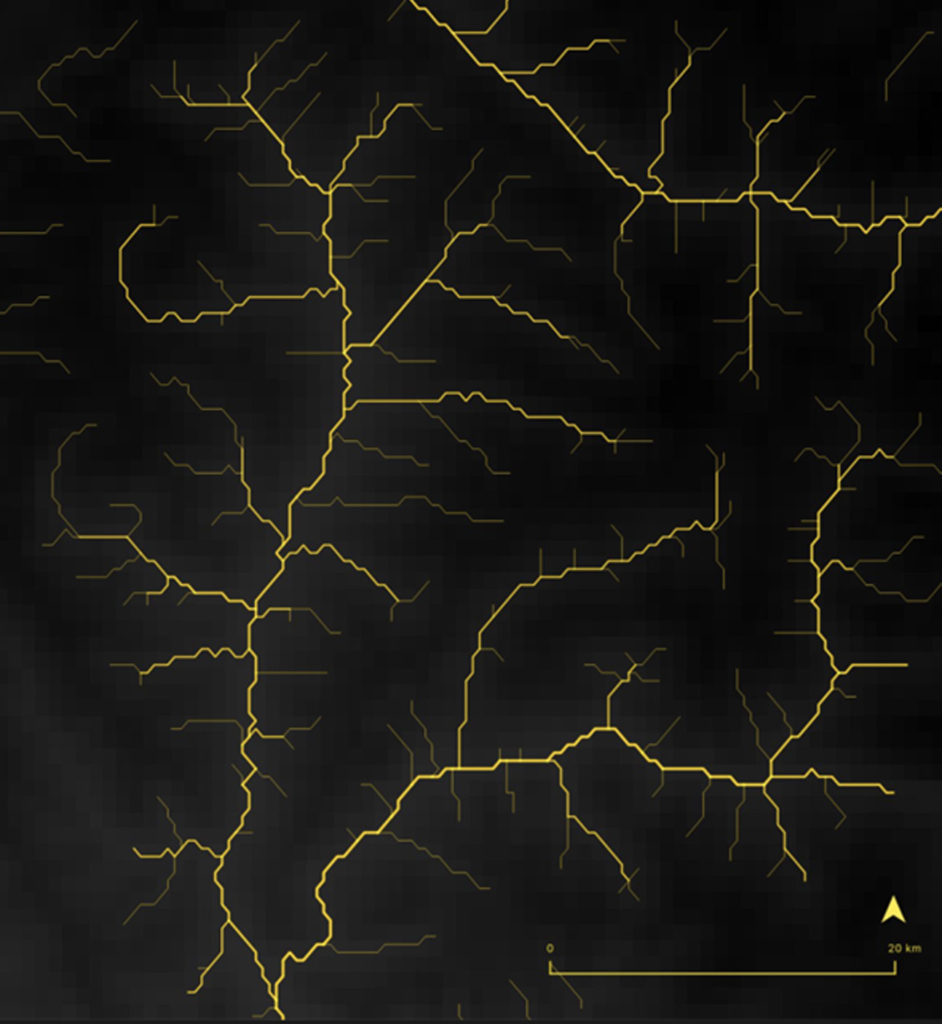

The Beas Book Club has decided to read Is A River Alive? by Robert Macfarlane. Considering the river that runs through the lives of all of us who live up here above the clouds in the Kullu Valley, this is an appropriate choice. One member has been taking photographs of the Beas in its many moods for over a decade. Another has just begun a river cartography project in which she maps the course of the river and its tributaries in gold, describing it as the ‘kintsugi’ holding together the ‘black ceramic’ of the Valley.

Sometimes, however, when our goddess rages, she tears things apart. The streams and tributaries above our homes go tumbling into the Beas way too fast, thanks to cloudbursts or a particularly heavy monsoon. Rocks start to tumble. Mountains shift their stance. All roads, tunnels leading from our usually tranquil (sometimes even celestial) realm become blocked. The mood of the river shapes our very perception of paradise.

Just over the high passes in Ladkah and Zanskar, the Indus begins its mighty flow, travelling through Pakistan until it reaches the Arabian Sea. I think back to 2011, when that force of Nature broke its banks after a cloudburst and completely changed direction. Unfortunate houses, lorries, lives in its wake were tossed up into the air, wrangled inside out. Corpses lined Leh high street. A box of toys and resources I had brought from the UK for a school in Shey was found buried in a classroom, miraculously saved by mud; but my suitcase of instruments was swept up in the deluge. I liked to think of it sailing full pelt and being finally washed up on some shore, undamaged. I imagined wide-eyed children opening it on a riverbank somewhere and discovering its musical contents, striking up an impromptu riverside concert.

Even in our lower altitude mountain town of Manali, the river has the ability to severely change lives. Two monsoons ago, after a sleek new road had been inaugurated after five years of labour, rain and river, lightning and waterfall conspired to crumble it back into the Beas. A journey to Dharamsala that usually took around nine hours now took twenty-two. And so I come to Is A River Alive? with my answer fully formulating before even opening it. Yes, she lives. Yes, she is powerful. Yes, she must be obeyed.

I do not begin at the beginning, turning instead straight to Part II: Ghosts, Monsters and Angels, which I know to be the ‘India’ part of the book. In no small delight, I discover that it reads something like an extended Socratean dialogue between Robert and naturalist and intertidal defender of the shores, Yuvan Aves. It is also a conversation between the both of them and the rivers of Chennai. There is an amorphous quality to the narrative, an appropriate and necessary fluidity, blurring shore and water, security and emotion, meandering through linguistics, politics, sociology, poetry, philosophy, history, arriving at the estuary that could be described as ‘political ecology’. Unlike Chennai’s choked and tortured waterways, this story never gets blocked. Moreover, it unblocks me.

I am in floods by the time I reach the end of Part II, the nighttime Turtle Patrol in which Robert, Yuvan and Arun Venkatraman walk all night to rescue turtle eggs from tractor tyres and scavenging pye dogs: eggs which may, in some distant reality, turn out to be our evolutionary future, actual universes within each unborn self. As I contemplate the enormity of this miracle, my rivers break their banks. I weep and weep over the book, immersed and overawed. How can the phenomenally beautiful Olive Ridley continue to honour our shores by blessing us, trusting Earth, with her precious clutch of eggs? She honours and trusts – but do we honour and trust her in return? The answer to that question sobs itself out, terror-stricken by the ghost nets waiting to catch her as she swims more gracefully than any dancer; disoriented by the blundering trawlers who change course for no man, let alone a goddess of the deep. I choke on the levels of radioactive and toxic waste that we expect, heedlessly, the offspring of our own species to swim, play and grow up in. Just how can this be possible? Just how can survival be possible?

Yet this vast body of a book does not give up on us. Rather, it offers dissolution as a possible solution: become one with flow, erase all man-constructed boundaries and honour the passage, as does the river in its unending memory, as does the turtle on her quest for planetary salvation.

Honour the moment.

Honour the flow.

Take time, as does she, to replenish. Go slow. Do not rush through these sacred tasks, the sacred task of being alive. Bring to it every mote of attention you can muster. And slowly, inevitably, the tide has to turn.

*

My sobs recede. I look up from reading Is A River Alive? across a valley of green forested slopes, recently made emerald by plentiful rain and behind them, cloud, high peaks and passes leading into the Zanskar Valley, birthplace of my husband, Tanzin and the Zanskar River, a tributary of the Indus. Thanks to several geographic quirks of fate, Tanzin met Robert and his family some twenty years ago when he first arrived in the UK. Robert had just written his first book, Mountains of the Mind and being a man of the mountains, Tanzin decided to write his MA thesis on this work. I helped him to edit the thesis, and thus was our romance- and my subsequent migration to the Indian Himalayas – sealed. One could almost say the mountains arranged our marriage.

I muse upon these chance or karmic meetings and readings, watching as wisteria curls its determined way around and around the balcony rail, a new frond each day, demonstrating just how rapidly our microcosm of a home would rewild itself, given half a chance.

Bewilderingly rapidly.

I sit out all morning thinking and writing under a sun too hot for the dogs who crouch in the shadow of a charpoy. I contemplate the Rights of Nature as per Ecuadorian constitutional law and consider the root of the verb ‘to bewilder’.

Be wild, I think, lose yourself as the book instructs in an undertone of linguistic mycelium. Throw out the old rules and hearken with your heart to the ancestral wisdom deep in the very water of your cells. As rivers remember, so do we. I look up to read cloud auguries declaring cumulous conversations above the lowest hills, involved, clustered, dense. Higher still, herringbone strata and windswept sheep’s fleece imply the teasing out of big ideas, the clearing of woolly thinking. And thereafter, deep blue. Clarity. Knowing through unknowing. The mighty Beas, with its source ( the Beas Kund glacial lake) just a little higher up the mountain, runs on.

I turn back to the beginning of the book, to Part I and Los Cedros, the Cloud Forest in Ecuador, where multispecies and dengue flourish. By late afternoon, I am finishing Part III, where the Great Lake of Mutehekau Shipu in Northern Canada flows into a tempestuous, lightning-quick river that corporations would give much to see dammed and indigenous First Nation people would be willing to die for. As Macfarlane makes his physical and spiritual journey downstream by canoe, he challenges us with more questions: What would salvation look like to you personally? A happy death? Enlightenment? Eco-justice? Beyond the grave meetings with loved ones? Or perhaps complete dissolution into emptiness as your atoms and cells disperse, as stardust, earthdust, to reform as underground rivers of networking fungi, reflected with equal luminescence by the passage in the sky we deem the Milky Way.

I am prompted to investigate what my own deep salvation feels like, smells like, encouraged to practice realisation of that wholeness, that unity with the other, be it lake or sky, river or tree, fellow human, book or idea, until I find peace. And what does that peace taste like, exactly? Just up the hill is the sacred village spring, flowing icy cold even on the most boiling of summer days. From here, great rivers begin, I think as I cup my hands and watch them fill with sparkling life force. Drinking deeply from the source, I too become River.

Tansy Troy is an India-based educationalist, poet, performer, playwright and maker of bird and animal masks. She conceived and edits The Apple Press, a young people’s eco journal which features poetry, stories, articles and artwork. Tansy has published poetry, articles and reviews in The Hindustan Times, The Hindu, The Scroll, Punch Magazine, Art Amour, Muse India, Plato’s Cave and The Yearbook of Indian Poetry in English. Join her on the journey @voice_of_the_turtle