By Andal Srivatsan

Nature and poetry have been linked for centuries before the genesis of the term romanticism. While the proverbial connotation of romance is rooted in love, attraction, and a deep sense of belonging, romantic poets wrote about striking rural landscapes as a source of joy.

Alfred Tennyson’s The Brook quotes the brook itself. It is human, delicate, undaunted and, most importantly, unchanging.

I chatter, chatter, as I flow / To join the brimming river, / For men may come and men may go, / But I go on forever.

The Earth and Human, as Companions

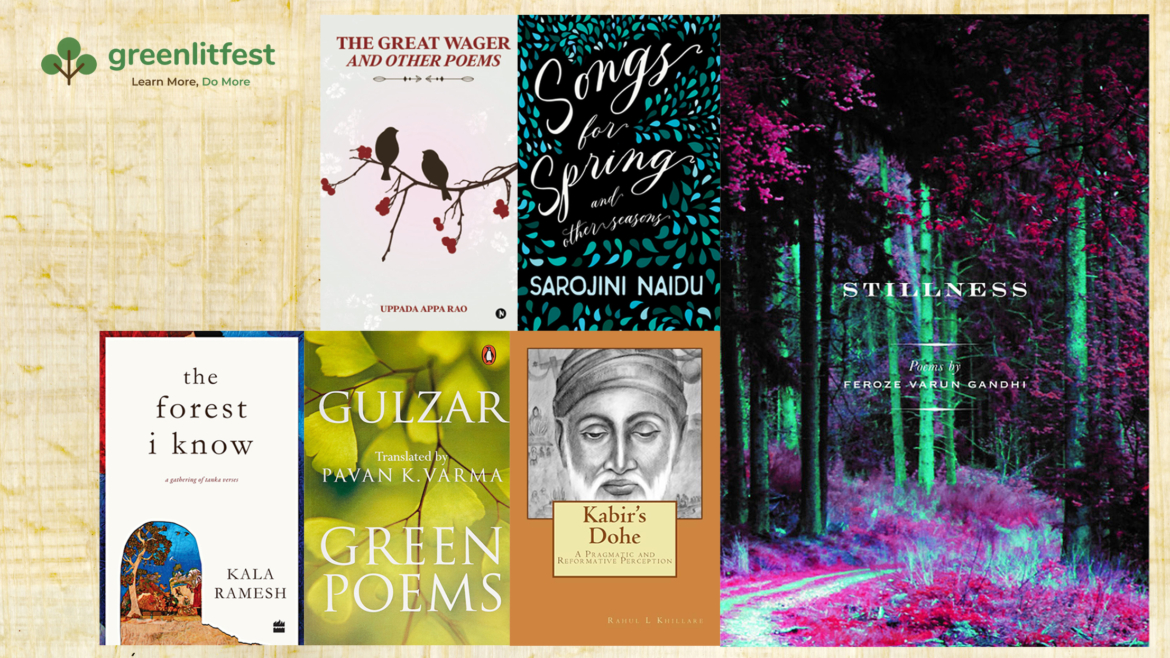

Gulzar’s 2014 Green Poems, translated by Pavan K. Varma, celebrates human’s congenital connection with nature. He writes about rivers, forests, the abundance of the earth, flakes of snow, but simply a glimpse. Gulzar’s poetry is a fleeting moment—a snapshot as one runs past a vista to capture it in memory, but alive through creative personification, like the stance of a leaf expressing solidarity with its comrades.

That one leaf, / Keeps telling the tree, / Don’t be afraid, I’m there! / Don’t be afraid, I’m there!

The love for nature trickles further down, as in the 2022 anthology The Great Wager and Other Poems by Uppada Appa Rao, reminiscent of the words of Keats or Wordsworth. In his poem The Sun, he chronicles the sun’s day, right from the moment the rays graze the skin to the time night arrives with gusto. In Rao’s poems, it is the sun that watches over azure fields, lovers meeting in secret, its reflection on the expansive sea, and it being chased by poets and painters for its vagrant moods. While we deem that vast green fields, sunny meadows, and bottomless oceans catch the poet’s fancy, it is perhaps the other way around. The fields, meadows and oceans watch upon us and string themselves into verses; big and small.

It is the fancy that envelops Kala Ramesh’s 2021 The Forest I know through simple, ardent tanka verses. It is through brevity and impressive locution that human truths are most visible, where one reaches the pinnacle—the enlightenment of self. In these tanka dohas, the readers walk alongside the poet through metaphorical forests created by the poet’s pen. These forests are vines of her life and the want for an illusory experience to serve as a coping mechanism. Poets have often borrowed from nature’s lap, extending a tree’s many roots, branches or leaves into our own homes, as a way of finding solutions amidst an entangled forest.

from a branch / silver threads stretch / into the unknown. . . / a search for keys to open / spaces that have no doors.

Poetry as an Anchor

The dohas themselves are reminiscent of the legendary Kabir; a master of metaphors and simplicity. His poems boasted of a worthy, wise afterthought and only chased one thing—truth. His description of bliss in his poem My Swan, Let Us Fly, speaks of a spiritual union with the divine, symbolised by the land where the beloved lies. This beauteous land that Kabir speaks of has rain without clouds, perpetual moonlight, a million suns, and sans darkness. It is idyllic. The mystical and devotional strands of Kabir’s utopia are the greater aspects of the world around him; the untouched natural paradise.

My swan, let us fly to that land / Where your Beloved lives forever. / That land has an up-ended well / Whose mouth, narrow as a thread, / The married soul draws water from / Without a rope or pitcher.

More often than not, the struggles of our times are collected in verses, as was the case with the Indian Freedom Movement, and the words of many writers, including Sarojini Naidu. In the 2020 collection Songs for Spring and Other Seasons, Naidu’s memorable work was a reflection of her ideals—women’s emancipation, civil rights and anti-imperialistic ideas, all to snatch the country away from colonial rule. In A Song in Spring, she juxtaposes nature’s ephemeral beauty against the more intricate aspects of human life and endurance. While nature rests in its blithe transience, humans grapple with sorrow, dreams, ageing and death.

But the wise winds know, as they pause to slacken / The speed of their subtle, omniscient flight, / Divining the magic of unblown lilies, / Foretelling the stars of the unborn night.

The reality of humanness was decorated in Feroze Varun Gandhi’s 2015 collection, Stillness. His introspection is told through emotional landscapes that mirror nature’s landscapes. In his poem Afterglow, the passage of time is explored through the jungle; its nights and sunrises. The transition in one’s life is comparable to the various births and deaths around us, just as they ease into the mornings or quiet into the nights.

Wrath in Verses

There is no end to inspiration in the natural world, even when it suggests destruction. As trees are felled around us and rivers transform into mere droplets, poets have epitomised the destruction of the earth in more ways than one. Jamaal May’s Water Devil explores the duality of existence. Here, beauty and destruction live together. Nature nurtures and destroys. The violent image of a hurricane is contrasted with the delicate image of a raindrop rolling down one’s back.

Spout of a leaf, / listen out for the screams / of your relentless audience: / the applause of a waterfall / in the distance, / a hurricane looting / a Miami shopping mall. / How careful you are / with the rain-cradling / curve of your back.

The destruction, however, is human’s doing. Our sprawling cities, fleet of cars, and swarm of ignorance have only depleted resources. On streets or pages, poets weep over the mass mutiny. Count Every Breath: A Climate Anthology, edited by Vinita Agarwal, brings forth voices that mourn the world’s downfall. What would it take for humans to recognise the unconditional, irrevocable love we bear for a tree? If not a sermon, perhaps a couple of verses that communicate heart-wrenching truths. Mani Rao’s poem, Lately, the Colour of Water, is a truthful and brutal reminder of our obliviousness.

But when sewage raids / artesian wells / and tap water’s the colour / of chocolate / It’s too late for / survival games.

Parting Note

Humans first arrived over six million years ago, and the first poet is believed to be Enheduana from 3400 BC, an unfathomable amount of time ago. The scripts were found on clay tablets in Sumerian. Even then, her reverence for Inanna, the Mesopotamian goddess of love, war, and fertility, took the shape of natural forces.

You are like / a flash flood that / gushes down the / mountains / Raging rainfall of / fire! It was An who / gave you power.

Power, deities and the heavens could only be comparable to something supreme, like nature. The gushing of floods down the mountains and furious rainfall depict something greater than being. It is this greatness that artists have sought to preserve perpetually since the dawn of mankind, maybe not in form, but in words.

Andal Srivatsan is a writer and poet based out of Bangalore, India and the editor of Pena Lit Mag. Her work has been published in various places – TBLM, Verse of Silence, From My Window, The Chakkar, A Thin Slice of Anxiety, BlazeVOX, The Sunflower Collective, Tarshi’s In Plain speak, Mean Pepper Vine. She can be found on Instagram @andalsrivatsan, where she writes book reviews and poetry frequently.